Glossary

AMR: Antimicrobial Resistance, which occurs when a microbe or pathogen genome evolves or acquires genes or plasmids that confer resistance to an antimicrobial.

Antimicrobials: agents (e.g drugs) that can interrupt the life cycle or replication of a microbe or pathogen.

Endemic: refers to a disease that is prevalent in or restricted to a particular location, region, or population.

Epidemic: is an increase in the expected number of cases of a disease in a particular population and area.

HIC: High-Income Countries, which is defined as a group of countries with highly developed economies by the World Bank classification.

Limnology: the study of aquatic ecosystems in inland waters such as lakes, reservoirs, rivers, streams, wetlands and groundwater.

LMICs: Low-and-Middle-Income Countries, a group of countries with less developed economies by the World Bank classification.

MDR: Multidrug-Resistant, which refers to genes or pathogen strains that confer resistance to most or all available antimicrobials.

NCD: Non-Communicable Disease, a disease that is not transmissible from one person to another. Instead, they are the result of a combination of genetic, physiological, environmental and behavioural factors.

NGS: Next-Generation Sequencing, a high-throughput sequencing methodology.

ONT: Oxford Nanopore Technologies, a sequencing technology company. Their sequencing platform is also referred to as ONT.

Outbreak: is a sudden increase in the expected number of cases of a disease in a limited area.

Pandemic: refers to an epidemic that has spread over several countries or continents, usually affecting a large number of people.

Plasmid: in nature, this is a small circular double-strand DNA molecule that can benefit survival or selective advantage to bacteria.

RT-qPCR: Reverse Transcriptase Quantitative PCR, also known as reverse transcriptase real-time PCR. A PCR method to quantify RNA copies present in a sample; includes a step to synthesise cDNA from the template RNA before the PCR amplification.

SEDRIC: Surveillance and Epidemiology of Drug-resistance Infections Consortium, a genomics working group to monitor drug-resistance.

TB: is the acronym for tuberculosis, a lung infectious disease caused by the pathogenic bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Transposon: is a DNA fragment that can change its position in a genome through cellular mechanisms.

VOC: SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern, a viral variant with mutations that confer a beneficial feature to the virus, e.g. increased transmissibility or virulence.

WASH: Water, Sanitation and Hygiene, a commonly used term among stakeholders advocating for universal access to WASH, especially in resource-limited settings.

WGS: Whole-Genome Sequencing, a method of determining the entirety, or almost the entirety, of an organism’s genomic DNA sequence all at once. This entails sequencing all of an organism’s chromosomal DNA, as well as, DNA found in mitochondria and, in plants, chloroplasts.

Pathogen monitoring

In this video, Dr Josefina Campos shares her experiences and explains the importance of genomics surveillance to monitor and control pathogen outbreaks.Working together to build capacity

In this video, Dr Tomas Poklepovich Caride from the National Center of Genomics and Bioinformatics, Argentina, tells us what the requirements for efficient pathogen monitoring in a laboratory facility are, including storage space and bioinformatics.

A robust healthcare system and infrastructure are vital for prevention, preparedness, early detection and response to pathogens. Thus, it is necessary to build a robust, comprehensive, and integrated surveillance programme.

Although the efficient implementation of surveillance programmes needs to consider social, economic, environmental, and technical conditions in the health landscape, not all surveillance systems are suitable for all countries or regions. Robust surveillance programmes depend on national healthcare infrastructure at the primary and reference level, as well as logistics, political and geographical realities.

The emergence of new diseases, conditions and events drive the review of public health priorities and strategies. After the COVID-19 pandemic, the incorporation of new technologies, including genomics surveillance and new networks added another level of complexity to pathogen monitoring.

The One Health concept has been increasingly discussed in the past two decades. It leverages a global health security approach by improving coordination, collaboration, and communication at the human-animal-environment interface. One Health addresses global health threats such as zoonotic diseases, antimicrobial resistance, and food safety among others.

To extend surveillance approaches, it is essential to engage and apply multi and transdisciplinary expertise. For example, a limnologist represents a valuable asset to better understand the ecology of vector or waterborne diseases. However, anthropologists could be advantageous in a field investigation, as the relationship between the community and the water is completely different according to history and cultural backgrounds.

One of the major lessons learnt from the COVID-19 pandemic is that multidisciplinary teams are key to responding to a global threat. The scientific community working together with epidemiologists, public health laboratories, stakeholders and decision-makers was essential for a strong pandemic response.

In the context of genomic surveillance, bioinformatics and IT team members must be included in the decision-making process, so that they can rethink the informatics architecture and ensure that translate genomics results to feed the surveillance systems into measurable actions. We also need to consider how to develop a surveillance system that engages with national reference laboratories, provincial or regional laboratories, academics and universities, for all, will input genomics information into the system.

Although access to core genomic facilities and bioinformatics expertise is still limited in public healthcare facilities in low-and-middle-income countries and many in high-income countries, the need to respond to COVID-19 enabled the improvement of genomic structures across the globe. These resources can be repurposed to provide genomic surveillance response of all pathogens of public health importance and also some non-transmissible diseases diagnosis.

Effective disease surveillance requires the collaboration of multiple teams, including genomics specialists, disease reference laboratories, bioinformatics, epidemiologists, and physicians; they also need to be aligned with national plans, which can add another layer of complexity. The challenge encountered by multidisciplinary teams includes not only disease detection, long-term surveillance, data reporting, management and analytics. They also must liaise with other stakeholders, including industry, and need to be prepared for information dissemination, logistics and continuous capacity building and training.

The pharmaceutical industry also played a major role in the COVID-19 response team in vaccine development and scale-up production. Industry capacity needs to be considered in the surveillance scheme of each disease’s dynamics. For example, if we are implementing a vector control strategy, it’s important to consider:

Is the industry able to provide the insecticide chosen?

Is it available for local production? If not, can it be promoted by the programme?

What genomic data could tell us

In this video lecture, Prof Philippe Lemey uses phylogenetic data to show how genomic data can be presented and how to interpret it.

Note: HBV - Hepatitis B Virus

Transferring knowledge

In this video, Prof Christine Carrington from the University of the West Indies, Trinidad and Tobago, Dr Emma Hodcroft from the Universities of Bern and Geneva, Switzerland and Dr Richard Orton from MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research, United Kingdom discuss with Dr Thanat Chookajorn relevant questions on how we can use genomics to improve the surveillance of pathogens of public health relevance. They discuss the importance of training, education and the transference of knowledge to laboratory teams and academic researchers.

Laboratory quality management

In this video, Dr Ana Filipe from MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research, United Kingdom and Dr Harper VanSteenhouse from BioClavis Research, United States of America talk about quality control and standards that can be used across a national laboratory network.

To ensure that laboratories provide results that reduce the risk of errors and are both accurate and reliable, it is important to implement a Quality management system (QMS). However, in resource-constrained settings, most laboratories are not accredited and may only be partially implementing elements of a QMS. Introducing a new test, particularly under outbreak conditions, may therefore come with a high risk of errors. This step describes the key critical elements that laboratories should put in place to ensure quality results in less optimal conditions, such as during outbreaks of COVID-19.

Quality Control (QC) is a mechanism that monitors the analytical performance of the test when used with or as part of a test system. It may monitor the entire test system or only one aspect of the test. QC validates the competency of testing laboratories by assessing sample quality and monitoring test procedures, test kits, and instruments against established criteria. It also includes the review of PCR results and documentation of the validity of testing methods. QC is therefore a multi-step process with certain checkpoints throughout the testing process: pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical stages. In general, QC should be performed regularly to detect, evaluate, and correct errors due to test system failure, environmental conditions, or operator performance before reporting test results.

QCs that are commonly employed for PCR testing include extraction negative control (checks contamination at extraction phase), extraction positive control (checks extraction process-reagents and equipment functionality), non-template control (checks contamination at PCR phase), positive template control(s) (check(s) limit of detection and robustness of the assay). Commercial QCs for positive controls are preferred, however, laboratories can use patient samples with known viral RNA concentration, preferably samples with low cycling threshold (Ct) values (25–30) for the target sequences of SARS-CoV-2. Nuclease-free water or viral transport medium can be used as the negative control. QC failures, for example, when a positive control turns out negative or a negative control turns out positive, invalidate the test results. Common causes of failure include contamination, degradation of samples, and expired reagents. After investigating and fixing the cause of the QC failure, the test must be repeated using either stored or newly collected samples.

External Quality Assessment (EQA) is a process that allows laboratories to assess their performance by comparing their results with those from other laboratories within the network (testing and reference laboratories) via panel testing and retesting. EQA also includes the onsite evaluation to review the quality of the laboratory’s performance. It usually evaluates testing competency, the performance of the laboratories, the reliability of the testing methods, and the accuracy of the results reports, including following up on any unacceptable EQA results with corrective action. One or more of the following three EQA methods can be applied to COVID-19 molecular testing laboratories:

Proficiency testing (PT) is when an external provider sends a set of SARS-CoV-2 positive and negative simulated clinical samples for testing in different laboratories and the results of all laboratories are analysed, compared, and reported back to the participating laboratories. Laboratories should select PT providers with a track record in delivering PT panels within their region.

Retesting refers to samples that have been tested at one laboratory and are then retested at another laboratory, allowing for inter-laboratory comparison. A laboratory’s first positive COVID-19 sample should be sent to another testing laboratory, preferably a national or a WHO reference laboratory. In the absence of PT, national COVID-19 laboratories should send five positive and ten negative samples, systematically selected, to WHO reference laboratories for retesting. Similarly, sub-national COVID-19 testing laboratories should send retesting samples to their national COVID-19 reference laboratory.

Onsite evaluation should be performed by experienced subject matter experts, who observe and assess the quality management systems of the COVID-19 testing laboratories across the three testing phases. Onsite evaluation includes Patient Management, Biosafety adherence, Quality control procedures, Staff competency, Sample collection procedures, Standardised testing policies, Documentation and maintenance of records. Onsite evaluation should be conducted at least once every twelve months, but preferably every three to six months.

Download Guidance for SARS-CoV-2 surveillance in Africa from the African Union here

Why biobanks are important

A biobanking system that collects, stores and archives specimens (e.g. viruses or other pathogens) to facilitate the development of diagnostic tests and evaluate diseases with pandemic potential can be crucial to public health responses. But what is a biobank? In this video, Gideon Nsubuga walks us through the Integrated Biorepository facility of H3Africa at Makerere University, Uganda. You will find out that biobanking is a lot more than a freezer farm.

Just like how a bank accepts (receives) and safeguards (stores) money owned by other individuals and entities, and then lends (gives out/shares) this money in order to conduct economic activities or simply to cover operating expenses (value addition), biobanks receive and store biological samples and health information. This is done in an ethically and legally regulated manner, and biobanks share these samples with researchers who can conduct research and investigate diseases using them.

What is a biobank?

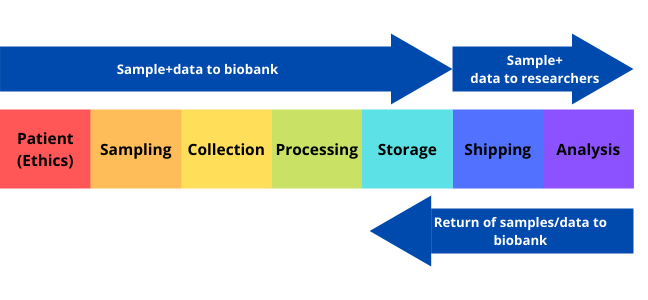

A biobank/biorepository/bioresource is a collection of biological samples and health information. The purpose of a biobank is to process, organise, and maintain various types of biospecimens that are shared for utilisation in both clinical and research-based services (Figure 1).

Click here to enlarge the image

Download Figure 1 alt-text here

Different biobanks collect different types of samples and information. The types of information and samples collected depend on the specific purpose of the biobank. For example, some biobanks are specific to a particular disease, such as cancer. Other biobanks are population-based and contain samples and information from people in a specific population or region. The biobanks have become a crucial resource for medical research since the late 1990s as they support various sectors of research, such as the field of personalised medicine and genomics. In fact, TIME magazine listed biobanks as being among the ten big ideas changing the world. Biobanks allow researchers to access biospecimens and data that represents a large number of people, and this can subsequently be used by multiple researchers for cross-purpose research studies.

Biospecimens

Biospecimen types that are available include organ tissue, blood, saliva, urine, skin cells, and other tissues or fluids taken from the body. The samples are maintained in appropriate condition to prevent deterioration and are protected from both accidental and intentional damage. The sample is registered in a computer-based system. The physical location of the specific sample is also noted to enable the specimen to be easily located when required. Samples are de-identified to ensure donor privacy and allow researchers to analyse without bias. Room temperature storage may be used in some cases due to cost efficiency and so as to avoid issues such as freezer failure.

Ethics

Biobanks can only store and share samples if they follow the required ethical guidelines. Some ethical issues around biobanking are the ownership of samples, ownership of derived data, the right to privacy for donors, the extent of donor consent, and the extent to which information the donor can share upon the return of research results.

How does a biobank make performing research easier?

The biobank serves as a library for researchers. Therefore, the time and resources needed to recruit new participants for each research study are greatly reduced because samples and the corresponding medical information are already available in one place. By making sample collection and patient recruitment more efficient, studies can be performed more quickly and with greater quality control.

Metadata

Click here to enlarge the image

Source: Hugh Fox III

Donwload Figure 2 alt-text here

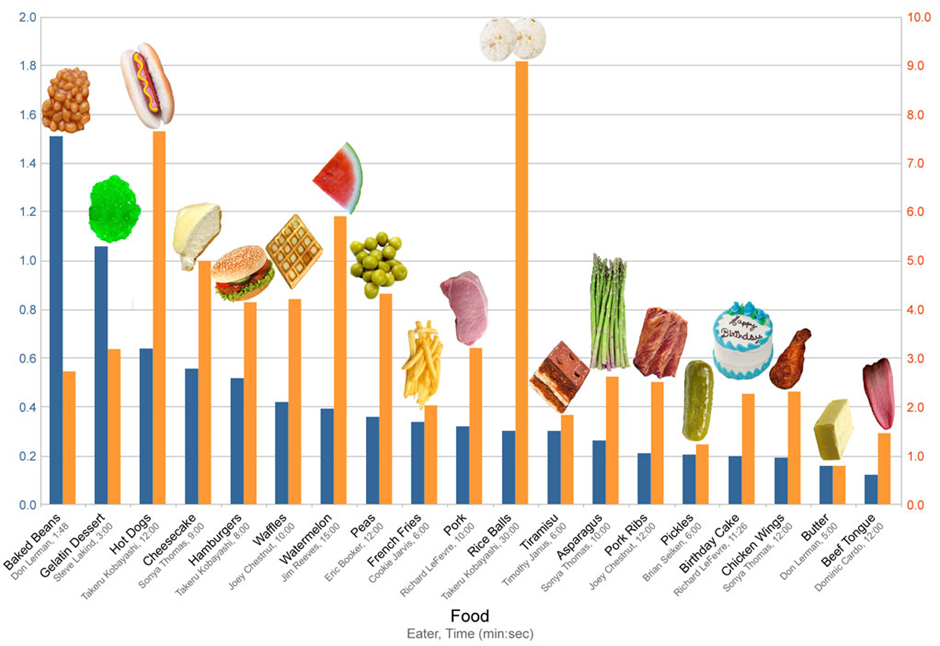

Imagine coming across this interesting-looking graph in Figure 2 above, but not knowing exactly what it’s trying to show you. The heading which read: “Competitive Eating Records” has been cropped off, and there are missing y-axis labels which should have shown that the yellow bars were the total weight of food ingested (kg) and the blue bars were the rate of ingestion (kg/min).

Most of you will be familiar with the concept of “garbage in; garbage out” (GIGO) in the context of ensuring good quality data. However, even if you have the best quality data, if your data has no context, you have no story.

So what exactly is metadata, and why is it important?

It is now easier than ever to access millions of sequenced datasets deposited in public databases. This mining of data enables us to do extensive meta-analyses to gain new and unexpected insights into the underlying biological mechanisms across viruses and the tree of life.

However, this process is often hindered by a lack of accompanying metadata. Metadata comprises any data that describes the sample type, collection procedure, extraction, assay methods used, analysis with the chosen parameters, filtering steps, quality control, reporting of software versions, as well as any other phenotypic descriptions.

Most of the time, some metadata is provided during data submissions, but this metadata is often unstandardised. A standardised format implies that there is a checklist which necessitates that a minimum amount of metadata must accompany the data and that free text is limited in favour of a controlled vocabulary.

The COVID-19 pandemic has especially highlighted how necessary it is to have informed data. Metadata such as the time and the place where the samples were collected, which may have not been as important to genomic datasets before, suddenly became crucial. Many repositories such as GEO and ENA now require research teams to use a metadata sheet with compulsory fields that must be populated when submitting data. Extensive efforts have also been made towards both manual curation and the automated assignment of metadata, through natural language processing (NLP) and the use of machine learning models.

Describing the WHO, WHAT, HOW, WHERE, and WHEN of genomic data also contributes to the findable, accessible, interoperable and reproducible (FAIR) guiding principles, to support the reuse of scientific data, and very importantly, it helps to inform public health responses.

Although we acknowledge the importance of accompanying genomic data with the appropriate metadata, we also have to be cognizant of the fact that the collection, anonymisation, storage and access to this data have to be carefully managed in a way that protects the donors. Submitting a data management plan as part of the research plan has therefore become an increasingly standard procedure.

The ethics of data sharing

Coordinated data sharing maximises the utility of data, which is critical for the control of infectious diseases. Data sharing is imperative during pandemics and public health emergencies. For example, many of the major achievements towards the containment of COVID-19 are attributed to the rapid sharing of sequence data across the globe. This step highlights some ethical considerations regarding genomic data sharing with examples from HIV phylogenetics and COVID-19 and presents some mitigation strategies.

Risk to privacy

Data sharing is widely used in HIV phylogenetic analysis. Balancing the benefits of understanding HIV transmission dynamics with the potential risks of harm arising from an unintentional breach of personal privacy remains a major ethical consideration in HIV phylogenetics. Such concern is justified considering that each HIV sequence is associated with a human being. While sharing HIV genetic sequences facilitates HIV-related research, it may worsen the risk of inferential privacy loss. These concerns should be viewed within the context of HIV social stigma and criminalisation of HIV transmission, which pose severe risks of social harm to research participants in the event of inadvertent disclosure of personally traceable results.

Equitable data use and benefit sharing

Apart from potential risks of harm to individuals, there are ethical issues regarding the fair use of valuable data generated and shared by researchers from low to middle-income countries (LMICs). While their contributions might be acknowledged, the scientific benefits that accrue from the analysis of the sequence data might be inaccessible to the communities that contributed data towards that benefit (e.g. vaccines not being available to those communities). This results in mistrust and uneven vaccine access, as witnessed during the H5N1 outbreak and recently the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, researchers based in LMICs should also receive appropriate credit for their contribution to eventual scientific publications.

Mitigation strategies

Several strategies can mitigate the risks posed by sharing pathogen genomic data. Before sharing, protocols for the deidentification or anonymisation of data are required. Only limited information should be published with each sequence, and additional information should be released using a strictly controlled access protocol. Controlled digital systems that facilitate collaboration instead of data sharing could be prioritised.

If data are to be released for research purposes, the study should meet the ethical principles outlined in the Emanuel Framework. Furthermore, researchers should comply fully with the information provided in the consent documents, which specify what and how data will be shared and reused unless otherwise authorised by local or international ethics guidelines. Material Transfer Agreements between institutions should also provide clear statements on benefit-sharing, especially how products from the research (e.g., therapeutics or vaccines) will be shared.

In conclusion, further ethical-legal scholarship (including empirical work) is warranted to determine an optimal ethical framework and a best practice model to guide HIV genetic data sharing and use, including for molecular HIV surveillance. Lessons learned (e.g., risk/benefit determinations) from such sharing during the COVID-19 pandemic should also be reviewed in this process.

Data sharing in a public health emergency

In this video, Dr Ewan Harrinson from Wellcome Sanger Institute and the University of Cambridge guides us through the differences between data sharing routinely and during a public health emergency.

It is widely acknowledged that sharing research data in a timely and open manner is crucial to furthering progress in science and healthcare. However, due to the diverse nature of different research approaches, systems, national guidance and field-specific practice, merely making data available does not always maximise the utility to the global community.

With these issues in mind, a group of researchers hosted a stakeholder workshop with experts from academia and the private sector in 2014 to discuss how to address the challenges. The workshop generated a draft set of principles guiding the sharing of data. They agreed that all research output should be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (FAIR). These FAIR guiding principles were subsequently expanded upon as below.

To be Findable:

F1. (meta)data are assigned a globally unique and persistent

identifier.

F2. data are described with rich metadata (defined by R1 below)

F3. metadata clearly and explicitly includes the identifier of the data it describes.

F4. (meta)data are registered or indexed in a searchable resource.

To be Accessible:

A1. (meta)data are retrievable by their identifier using a standardized communications protocol.

A1.1 the protocol is open, free, and universally implementable.

A1.2 the protocol allows for an authentication and authorization procedure, where necessary.

A2. metadata are accessible, even when the data are no longer available.

To be Interoperable:

I1. (meta)data use a formal, accessible, shared and broadly applicable language for knowledge representation.

I2. (meta)data use vocabularies that follow FAIR principles.

I3. (meta)data include qualified references to other (meta)data.

To be Reusable:

R1. meta(data) are richly described with a plurality of accurate and relevant attributes.

R1.1. (meta)data are released with a clear and accessible data usage license.

R1.2. (meta)data are associated with detailed provenance.

R1.3. (meta)data meet domain-relevant community standards.

These principles were published in 2016 and have been implemented widely across many fields since then. During the current pandemic, a number of groups have sought to consider how to implement these principles with the additional fast-paced pressure of an ongoing outbreak.

The Virus Outbreak Data Network (VODAN) established a project to develop an international data network infrastructure supporting evidence-based responses to the pandemic. One of the projects associated with VODAN has shown that this approach can be implemented in a hospital setting to allow rapid linking and sharing of relevant patient information in a machine-readable format. A further project highlighted the limited genomic data emerging from Africa underpinned by concerns around data ownership and availability of health data at the point of care. A system was developed to provide this data at the point of care as well as aggregated for global analysis and has been deployed in a number of African countries.

As well as the FAIR principles for data sharing, The Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group created a set of principles concerning indigenous data governance. These principles intend to maximise the benefits of data and research on individual communities, whilst promoting the outward sharing of data for global good in a manner that respects previous barriers to sharing and misuse of data. These principles state that there should be Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility and Ethics (CARE**). There have been subsequent efforts to guide the use of both FAIR** and CARE guidance in data usage (Table 1).

Table 1 - Implementation of the CARE Principles across the data lifecycle

| Practice CARE in data collection | Engage CARE in data stewardship | Implement CARE in data community | Use FAIR and CARE in data applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Define cultural data; record provenance in metadata | Use appropriate governance models; make data FAIR | Indigenous ethics inform access; use tools for transparency, integrity and provenance | Fairness, accountability, transparency; access equity |

Source: Scientific Data