LIBRARY PREPARATION AND SEQUENCING

@Canva

How to isolate good quality nucleic acids

The extraction of RNA from viral samples is an important step for pathogen research. Viral nucleic acid extraction is the first step for downstream genomic analysis. Analysis of viruses in biological and environmental samples requires efficient methods for viral nucleic acids that are amenable to a variety of sample types. Successful genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 depends on the quality of the nucleic acids extracted from the primary sample. Each sample type has unique requirements for optimal nucleic acid extraction and isolation.

Different types of samples are used for SARS-CoV-2 testing including:

- Swabs (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal)

- Saliva

- Sputum

- Other samples - bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and other respiratory research samples, urine, whole blood, plasma, tissue, stool, cell-free body fluids, and even wastewater

Due to the delicate nature of RNA, the RNA purification process consists of a variety of unique challenges, one of which is ribonuclease (RNAse) contamination. RNases are abundant in the environment and even a trace amount of RNase contamination can sabotage RNA-based experiments. Several precautions such as the use of RNase-free reagents, dedicated pipettes, glassware, gloves, and working in an RNAse-free environment need to be followed to achieve a good RNA yield.

Often minute amounts (low viral load per ml, typically 1000-5000 particles/ml) of viral RNA need careful extraction from samples such as tissues, nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swabs, sputum, blood, plasma, or other body fluids. Viral RNA might also be extracted from clinical samples, water or other environmental samples. Sometimes investigators might need to quantify the viral particles contaminating medicinal products such as vaccines. Since the viral load of these biological, medicinal, and environmental samples is usually exceptionally low, RNA isolation consists of two major steps: virus concentration followed by RNA extraction. Viral concentration is usually achieved by applying various precipitation, flocculation, and filtration techniques.

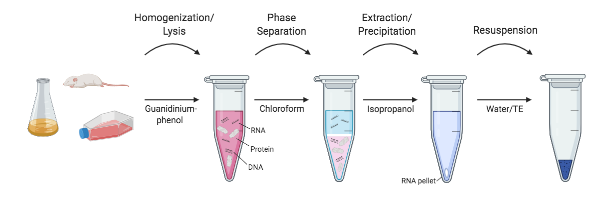

The Organic Extraction Method

The organic extraction method is the most tried-and-tested method for RNA extraction and removal of cellular proteins. Here, RNA isolation is achieved through organic extraction followed by RNA precipitation. This technique involves lysis or extraction in a monophasic solution of phenol and guanidine isothiocyanate. Chloroform is then added. The phenol-chloroform mixture is immiscible with water. Therefore, when centrifuged, the sample forms two distinct phases: the lower (organic) phase and phase interface contain denatured proteins, while the less-dense upper (aqueous) phase contains the RNA. The aqueous phase containing the RNA is carefully removed by pipetting, without touching the interface or the lower organic phase, as this can contaminate the sample. The RNA is then precipitated with isopropanol and then rehydrated for further analysis.

Organic extraction protocols are well-established and are useful for most sample types (Figure 1). Proteins are rapidly denatured, and RNA is quickly stabilised. The process is scalable and can be completed in 30-60 minutes. However, this method is not amenable to high-throughput processing and is difficult to automate. New users find the phase separation and careful pipetting of the aqueous phase challenging to master. A chemical fume hood is required due to the use of the hazardous chemicals, which then need to be disposed of appropriately. Manual handling of a large number of samples is cumbersome.

Download Figure 1, 2 and 3 alt-text here

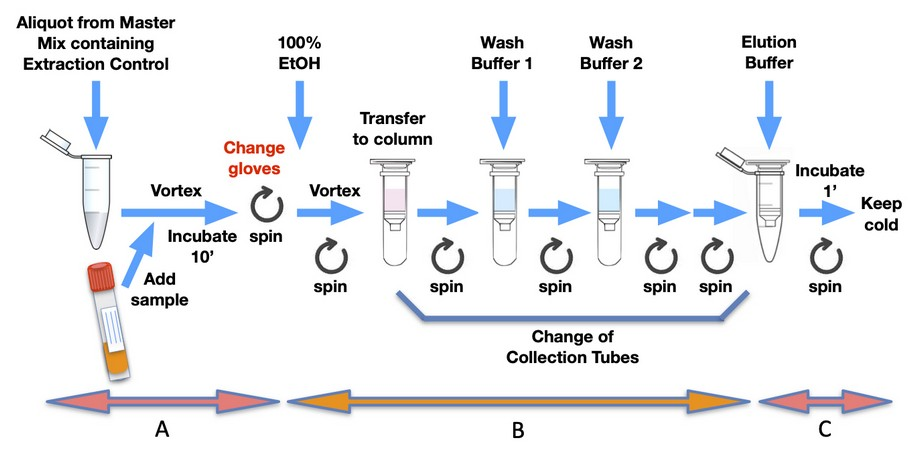

The Spin-Column Based Method

The easiest and safest method, readily available in a kit format, is the spin-column-based method (Figure 2). The binding element in spin-column systems is usually composed of glass particles or powder, silica matrices, diatomaceous earth, and ion exchange carriers. In this method, nucleic acid binding is optimised with specific buffer solutions and extremely precise pH and salt concentrations. Sample lysates are passed through the silica membrane using centrifugal force, with the RNA binding to the silica gel at the appropriate pH. The membrane containing residual proteins and salt is then washed to remove impurities, and the flow-through is discarded. RNA is subsequently eluted with RNase-free water.

Column-based RNA extraction is one of the best techniques among the options available, playing a vital role in ion exchange methods, as it provides a robust stationary phase for rapid and reliable buffer exchange and thus nucleic acid extraction. This method is fast and reproducible, and its main drawback is the need for a small centrifuge. Vacuum-based systems can also be used in place of centrifugation to separate impurities. Researchers can also combine the organic extraction method with the spin column method for faster and greater RNA yield. This method is fast (20 minutes) and amenable to large-scale and high-throughput processing, including automated methods. Protein or DNA contamination is possible if the sample amount is large or remains incompletely homogenised or lysed. Incomplete lysis can also lead to low yields of viral RNA. Automation can be complex and expensive due to the need for setting up centrifugation or vacuum-based separation systems.

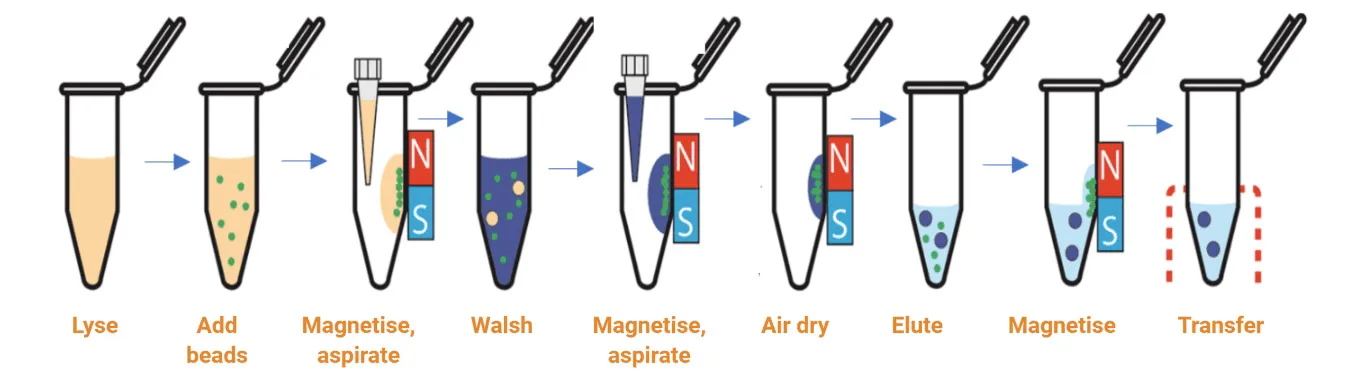

The Magnetic Bead-Based Method

The magnetic bead-based method relies on the use of magnetic beads and reagents optimised for RNA extraction (Figure 3). The beads have a paramagnetic core, usually coated with silica for nucleic acid binding. The sample is lysed in a buffer with RNase inhibitors and then incubated with magnetic beads, allowing the particles to bind RNA molecules. The magnetic beads can then be quickly collected by being placed in proximity to an external magnetic field. The supernatant is removed, and beads are subsequently washed in a suitable wash buffer with the removal of the magnetic field. This process can be easily repeated for multiple washes. The RNA is eluted from the magnetic beads with RNase-free water into a solution, and the supernatant (containing the pure RNA) can then be transferred.

The magnetic bead collection steps are simple and quick to perform. There is a reduced risk of clogging as no column is involved. This technique is the most amenable to scale-up, high-throughput separation, and automation. The clean-up is more effective due to the movement of the beads. However, viscous samples could impede the movement of the beads and, occasionally, the final sample may be contaminated with magnetic beads. A magnetic stand is required for manual separation and a magnetic particle handler for the automation of this process.

Automated viral nucleic acid purification systems

For fast, easy, and effective high-throughput sample processing, RNA extraction protocols are automated. Automated viral RNA extraction protocols for the silica plate-based protocol use a vacuum manifold to achieve buffer flow/wash and are available for a variety of liquid handlers. Automated viral RNA extraction protocol for magnetic bead protocol uses a magnetic comb which carries the separated nucleic acids from the lysis step through wash steps and finally, viral RNA is eluted into an elution buffer.

Table 1 - Summary of key differences between spin column-based and magnetic bead-based viral RNA isolation

| Method | Organic extraction | Spin column-based | Magnetic bead-based |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purity | Medium | High | Highest |

| Organic solvent hazardous waste | Yes | None | None |

| Difficulties | Phase separation difficult for new users | Handling several samples is tedious. Centrifuge/vacuum required | Magnetic stand required |

| High-throughput friendly | No | Yes | Yes |

| Concern of clogging | No | Yes | No |

Important considerations

Precaution 1: Samples may be fresh or frozen, but if frozen, should not be thawed more than once. Repeated freeze-thawing of plasma samples will lead to reduced viral titers and should be avoided for optimal sensitivity. Cryoprecipitates accumulate when samples are subjected to repeated freeze-thaw cycles which may lead to clogging of the silica membrane used for purification.

Precaution 2: RNA extraction is a delicate process, as cells and the environment secrete high concentrations of enzymes that destroy nucleic acids, therefore, the process must be carried out in a careful and quick manner.

Further reading

Viral RNA Isolation Methods Reviewed: Spin vs. Magnetic

What a targeted sequencing protocol

Different targeted methods have been developed to library preparation and sequence full-length SARS-CoV-2 genomes from specimens containing both viral and human nucleic acids. Due to the size difference between the SARS-CoV-2 (~30kb) and human (~6.4 Gb) genomes, sequencing the sample without enriching or amplifying the viral genome could result in >99% of the sequencing reads being human.

SARS-CoV-2 WGS – amplicon sequencing methods

In amplicon sequencing, the SARS-CoV-2 genome is amplified by RT-PCR (reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction) on overlapping fragments, which can differ in length. The most commonly used primers are the ARTIC primers designed by Josh Quick (University of Birmingham) which produce 400bp fragments. Other primer designs include those used in the Oxford Nanopore Midnight protocol. Amplifying longer amplicons (as achieved with Entebbe primers) has the advantage of requiring less primer pairs to cover the full-length genome (which may reduce the number of times the primer design needs to be updated to incorporate new variants), although they are unlikely to amplify SARS-CoV-2 in degraded samples as well as the ARTIC primers. However, more amplicons mean more opportunities for amplicon dropout leading to technical artefacts in the consensus sequence. Amplicons are prepared for sequencing using commercially available library preparation kits or open-source protocols.

The tailed PCR method is a variation of the standard amplicon sequencing approach in which a second PCR step replaces the need for library preparation. Non-homologous sequences containing the information required for NGS are added to the end of the ARTIC primers (‘tail’) and are therefore incorporated into the amplified fragments. A second round of PCR using indexing primers generates fragments ready to be sequenced. This approach is cost-effective as there is no library preparation although the likelihood of contamination occurring may increase compared to some methods due to the second round of PCR.

The Wellcome Sanger Institute provided large-scale and high-throughput sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 for COG-UK using a different tailed amplicon approach, whereby the first PCR step was with the ARTIC primers followed by a second PCR with a mix of tailed versions of the ARTIC primers plus the indexing primers.

The tailed PCR method has been further developed using a reverse complement-PCR strategy (RC-PCR) in which indexed libraries ready for Illumina sequencing are generated in a single PCR step. This approach has been used in the UK for monitoring SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater with an open-source protocol available .

SARS-CoV-2 WGS – bait/probe capture

In bait/probe capture the library is enriched for the viral genome using small fragments (baits/probes) complementary to the viral sequence which are then captured on a solid support. Various probe panels (both RNA and DNA) have been designed against SARS-CoV-2. An advantage of using this approach is that one bait set can be designed to target multiple viruses, for example, multiple respiratory viruses, meaning coinfections can be detected and sequenced from the same sample. Combined with deep sequencing, this approach can identify minority populations within a sample, allowing for analysis of the evolution of resistance mutations and informing treatment.

Further reading

CoronaHiT: high-throughput sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 genomes

Rapid turnaround multiplex sequencing of SARS-CoV-2: comparing tiling amplicon protocol performance

Mini-XT, a miniaturized tagmentation-based protocol for efficient sequencing of SARS-CoV-2

A rapid, cost-effective tailed amplicon method for sequencing SARS-CoV-2

Clinical and biological insights from viral genome sequencing

Improvements to the ARTIC multiplex PCR method for SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing using nanopore

How SARS-CoV-2 primer sets were designed

In this video, learn from Dr Naomi Park how to take into consideration genome coverage and viral evolution when designing primer sets for whole-genome sequencing.

Producing SARS-CoV-2 amplicons

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA) hold the genetic information required to make proteins, and therefore all life on earth.

The sequence in which DNA bases occur provides the genetic code. Some viruses, such as SARS-CoV-2, use RNA rather than DNA as their genetic material. To read the genetic code of SARS-CoV-2, its RNA must first be converted to DNA – allowing it to be ‘read’ by the sequencer. The conversion method used is called reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and it consists of two steps.

The first step synthesises complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA by reverse transcription (i.e the opposite of transcription). In this process an enzyme (reverse transcriptase) adds complementary bases to the single-stranded RNA, creating cDNA. The second step is PCR, which amplifies the cDNA using an enzyme (DNA polymerase), creating enough double-stranded DNA to go into downstream library preparation for sequencing.

SARS-CoV-2 samples contain contaminating human material, so the ARTIC PCR is designed to amplify SARS-CoV-2 cDNA. This is done using a ‘multiplex tiling PCR’. A multiplex PCR is the simultaneous amplification of multiple targets, and ‘tiling’ means overlapping amplicons that can be aligned bioinformatically to determine the full-length genome. The SARS-CoV-2 ARTIC primer pairs each amplify 400b regions of the SARS-CoV-2 genome. The ARTIC primer pairs are split into two pools, with adjacent primer pairs in different pools to prevent primers from competing for the same part of the genome, hence creating a more efficient amplification. The result of the PCR is two pools of 400bp SARS-CoV-2 amplicons which are pooled and subsequently, the library is prepared for sequencing.

The ARTIC PCR is also different to a typical 3-step (denaturation, annealing, extension) PCR in that it has a combined annealing and elongation, thereby only having two steps. This annealing/elongation step is longer than typical PCR annealing and elongation times, which is required in multiplex PCRs as there are more primers to anneal, and more targets to amplify.

| PCR protocol step | Number of cycles | Typical 3-step | Multiplex 2-step |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial denaturation | 1 | 95°C 30s | not applicable |

| Heat activation | 1 | not applicable | 98°C 30s |

| Denaturation | 30 for Taq; 35 for ARTIC | 95°C 15-30s | 98°C 15s |

| Annealing | 30 for Taq; 35 for ARTIC | 45-68°C 15-60s | 65°C 5m |

| Extension | 30 for Taq; 35 for ARTIC | 68°C 1m per kb | 65°C 5m |

| Final Extension | 1 | 72°C 5m | not applicable |

Further reading

Protocol for a Routine Taq PCR

nCoV-2019 sequencing protocol v3 (LoCost) V.3

SARS-CoV-2 Genome Sequencing Using Long Pooled Amplicons on Illumina Platforms

Assay Techniques and Test Development for COVID-19 Diagnosis

Checking the quality of amplicons

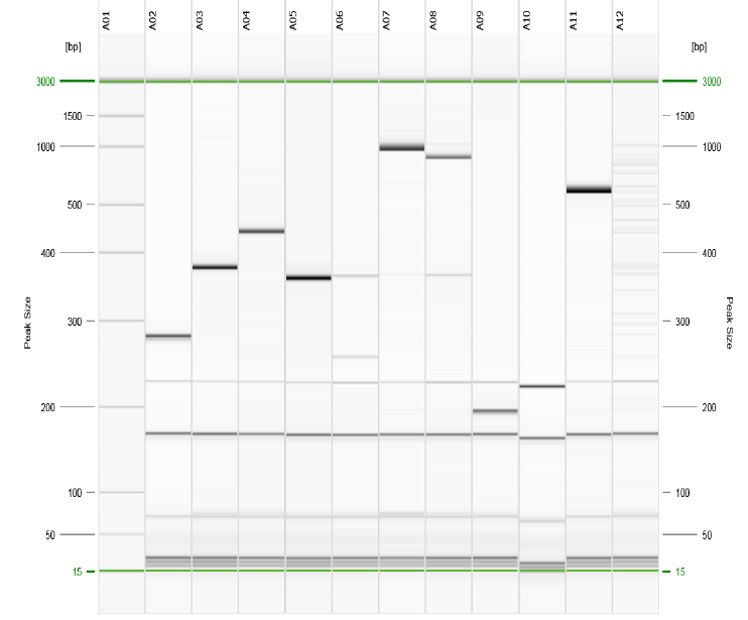

Genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 involves performing PCR using ARTIC or Midnight protocol. PCR amplification is the common step involved in both protocols. In order to confirm successful PCR amplification, PCR amplicons need to be analysed. Before pooling the PCR products obtained from Pool A and B, the PCR amplicons are either loaded on an agarose gel or QIAxcel to confirm successful amplification. The PCR products are then pooled and quantified using Qubit.

Depending on the information desired, there are different methods to analyse the products of a PCR reaction. Agarose gel electrophoresis, capillary gel electrophoresis and fragment analysis are the methods used to analyse the PCR amplicons. Mutation detection methods, such as denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and temporal temperature gel electrophoresis (TTGE), which use acrylamide gel to assist with identifying mutations in the PCR product, are also available.

Quality checks of the SARS-CoV-2 amplicons can be performed by:

- Running the PCR amplicons - Slab gel electrophoresis, Capillary gel electrophoresis

- Quantifying of PCR amplicons - Qubit

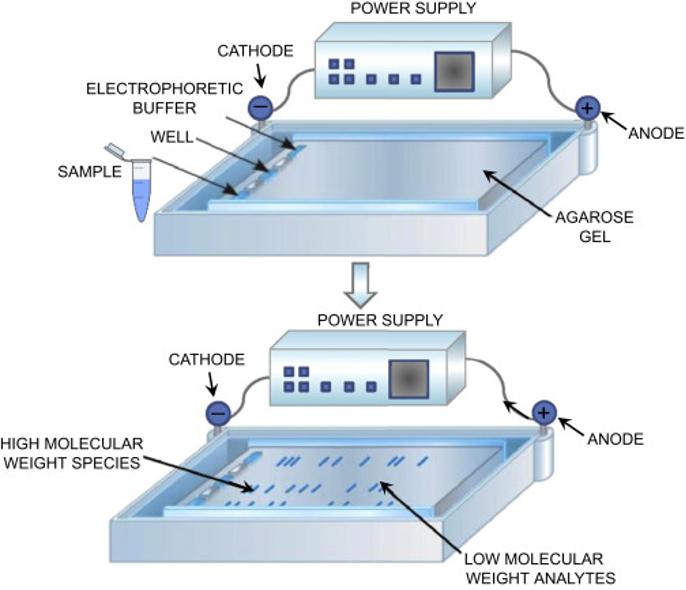

Agarose gel Electrophoresis (Slab gel electrophoresis)

Agarose gel electrophoresis is a common technique to detect the presence or absence of the target sequence and the length of the fragment (Figure 4). Nucleic acid fragments are separated by their length while moving through an agarose matrix. By adding a dye or an intercalating agent like ethidium bromide (EtBr), these fragments can be visualised under ultraviolet light. The intensity of the band can be used to estimate the amount of product of a given molecular weight relative to a ladder. Gel electrophoresis also shows the specificity of the reaction, where the presence of multiple bands indicates secondary amplification products.

Download Figure 4, 5, and 6 alt-text here

Slab gel electrophoresis (SGE) is a widely used technique for the analysis of PCR fragments. While SGE is a relatively inexpensive and easy-to-use technique, the amount of information, which can be derived with little effort from slab gels, is limited. Typically, size and concentration information is estimated by the scientist through visual comparison to the appropriate size and mass ladders which have been run in separate lanes on the gel. These estimations might be appropriate for experiments where a simple yes-or-no answer is adequate.

While gel electrophoresis is relatively easy to adopt in any laboratory, it has a number of disadvantages, including highly labour-intensive preparation of slab gels, and user exposure to hazardous chemicals such as ethidium bromide as a staining agent. Moreover, separation times can be rather long, depending on the experimental settings, and slab gels usually do not provide the high resolution required to meet today’s research demands.

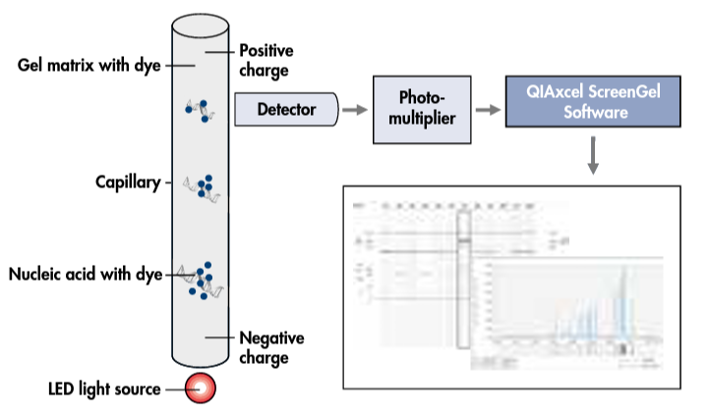

Capillary gel Electrophoresis (CGE)

Separation of analyte ions via differential migration in an electric field, coupled with the electro-osmotic flow of the mobile phase. Capillary electrophoresis (CE) is a process used to separate ionic fragments by size.

There are two different forms of capillary gel electrophoresis:

- Sequencer-based CGE

- QIAxcel-based CGE

Sequencer-based CGE (SCGE)

Sequencer-based capillary gel electrophoresis (SCGE) as an alternative to conventional gel electrophoresis, using 5′-end fluorescein-labelled primers and the AB 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, USA) with a 41-cm capillary loaded with a POP4 gel. This method was highly reproducible (the standard deviation of peak sizes was ±0.5 bp), independent of the reagents used, and had much higher discriminatory power than conventional agarose gel electrophoresis.

The use of fluorescein-labelled primers increases the sensitivity and, also, the cost of the method. SCGE requires access to a DNA sequencer, which may cause a delay if PCR products are referred to an external sequencing facility, and the cost of consumables per isolate is greater ($6 to $7, including primers, labels, PCR reagents, and SCGE, including a component for equipment cost) than for QCGE. SCGE requires the use of a more expensive instrument.

SCGE is not used for analysing the SARS-CoV-2 PCR amplicons, as SCGE requires fluorescent tagging of the primers.

QIAxcel-based CGE

The automated commercial CGE method, QIAxcel (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), is used in many SARS-CoV-2 studies for analysing the PCR amplicons, which does not require the use of fluorescein-labelled primers (Figure 5).

QIAxcel is an automated electrophoresis platform that can deal with up to 96 samples per run with high efficiency and a turnaround time of 0.2 to 1.5h depending on the number of specimens. It is simple to perform, and potentially suitable for a clinical laboratory.

The results can be exported in either electropherogram or gel-view format (Figure 6). The major costs are for the setup of the QIAxcel system hardware and BioCalculator analysis software and for consumables (cartridges), making the cost per sample around $3 to $4. However, compared with SCGE, QCGE has limited sensitivity and discriminatory power, making it unable to clearly distinguish between amplicons with a 3-5bp difference.

Advantages and disadvantages of PCR amplicon analysis methods

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Agarose gel electrophoresis | Inexpensive; Easy to use technique; Cost effective | Unsafe when EtBr is used; Low resolution; Time consuming; Labour intensive; Requires high concentration of Nucleic acids for detection |

| Capillary gel electrophoresis | Rapid analysis of up to 96 samples without manual intervention; Safe and Convenience with ready-to-use gel cartridges l; Robust results for nucleic acid concentrations as low as 0.1 ng/µl; Standardised and accurate analysis with a resolution down to 3–5 bp | Expensive compared to SGE |

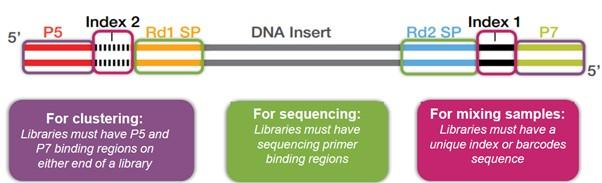

What is a sequencing library and how is it prepared?

Next-generation sequencing has revolutionised genomic research, allowing high-throughput profiling of genomes, transcriptomes, DNA-protein interactions and more. This is achieved by performing millions to billions of massively parallel short read (50-500bp) reactions in each run. In order for this to happen, each reaction must first be localised to a solid substrate, such as a bead or a glass slide, before being clonally amplified and sequenced in-situ. On Illumina systems, this process is referred to as clustering.

Before sequencing can begin, DNA or RNA samples must first be converted into molecules compatible with the sequencing platform of choice. We refer to this converted sample as a library, and the processes used to generate it are referred to as library preparation. Optional steps can be added before, during and after library preparation in order to enrich, select, deplete or convert the sample for specific content prior to sequencing (for example to enrich for pathogen DNA over host DNA).

If the input is RNA, such as for the SARS-CoV-2 virus genome, it must first be converted to DNA – a process known as reverse transcription. From here, there are three common steps in library preparation, summarised as follows:

1. Fragmentation and end-repair

Short-read sequences, such as Illumina, do not read long DNA fragments, so molecules must be fragmented to typical lengths of 100-300bp. Fragmentation of DNA can be performed physically, chemically or enzymatically. After fragmentation, these molecules require blunting, (so that each strand is of equal length with no unpaired bases), phosphorylation and A-tailing. Phosphorylation and A-tailing allow for T-tailed adapters to be ligated at the next step.

2. Adapter ligation

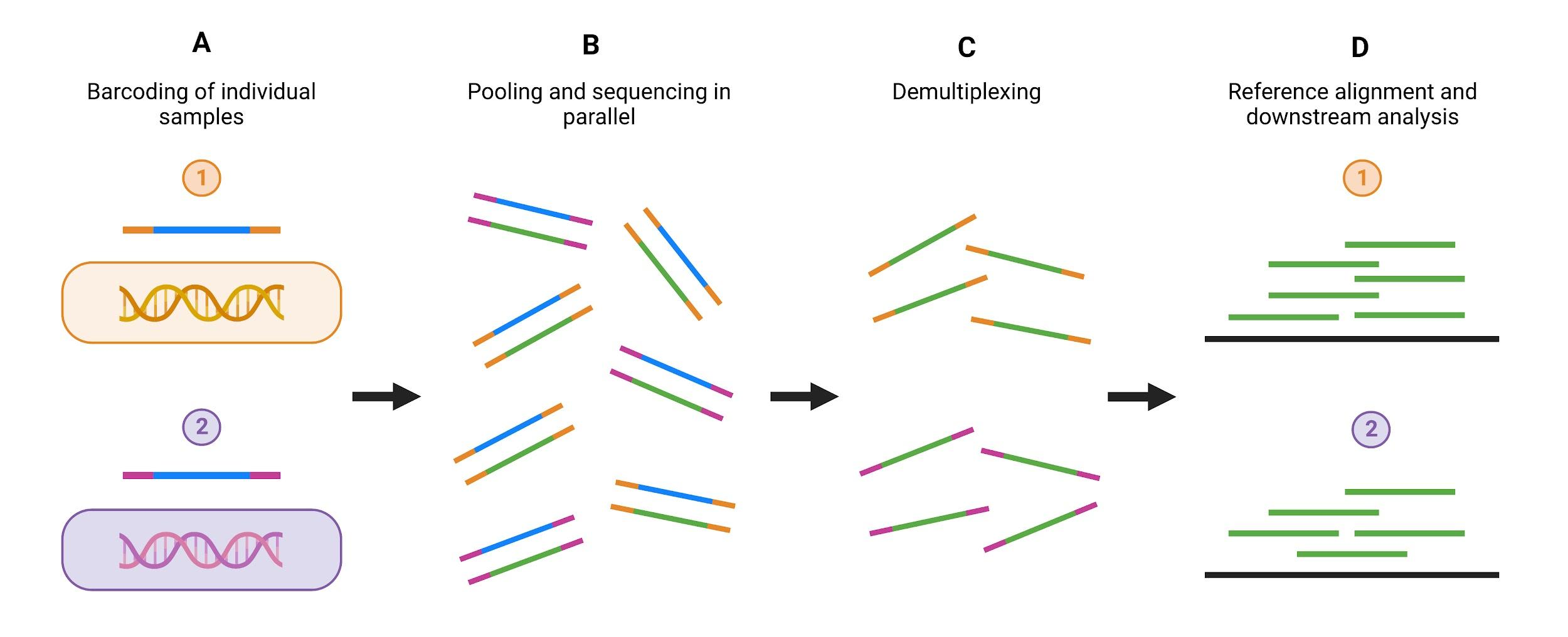

Synthetic DNA molecules, known as adapters, are attached to the ends of each library molecule. These adapters have multiple functions, containing domains to allow each molecule to be immobilised and amplified, along with domains for sequencing primer binding and domains containing sample-specific indexes. The use of sample indexes allows for many samples to be pooled prior to sequencing, thus maximising the output of each sequencing run. This is known as multiplex sequencing.

3. PCR amplification (optional)

PCR can be used to select library molecules that have successfully ligated adapters at each end, whilst boosting library yield for sequencing (Figure 7). P5/P7 and index sequences can also be added at this step, if not added at the adapter ligation step. PCR can cause bias in sequencing libraries as GC-rich sequences do not amplify well. If DNA input is sufficiently high, this step can be skipped, reducing PCR bias.

Download Figure 7 and 8 alt-text here

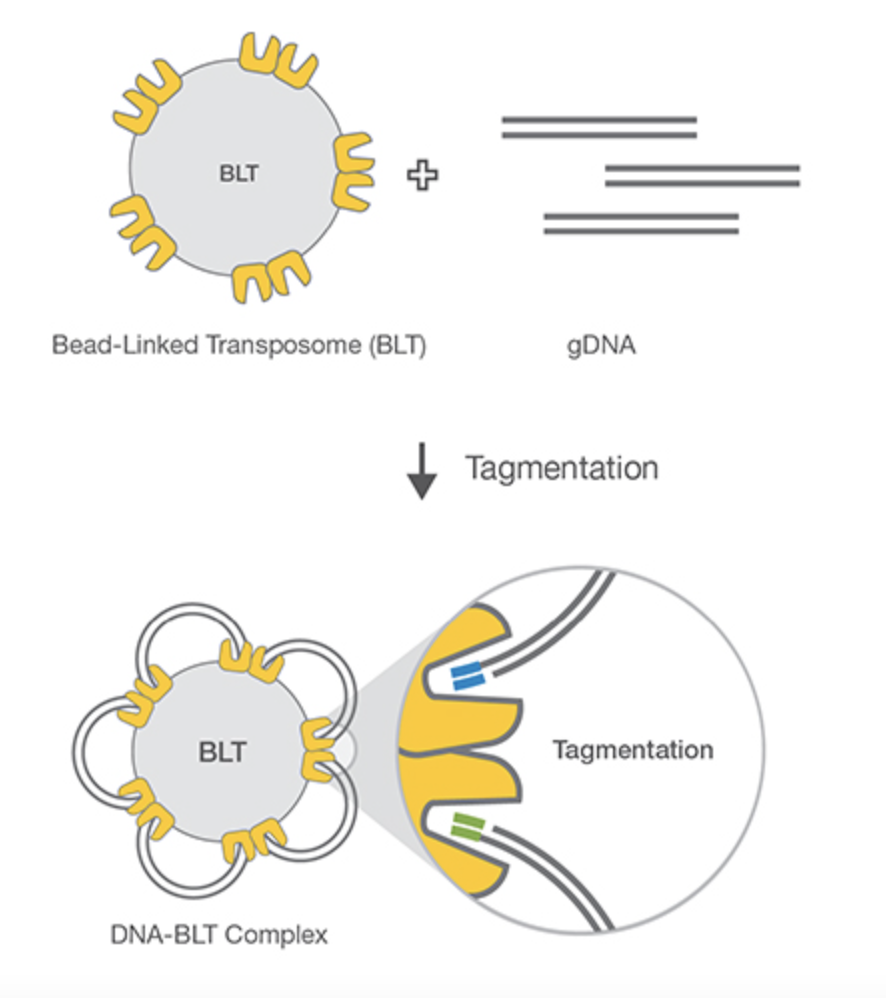

4. Tagmentation

An alternative method to the more traditional fragmentation and adapter ligation is a process known as tagmentation whereby a transposome (transposase enzyme plus DNA adapter sequence) simultaneously fragments and adapter tails DNA (Figure 8). Transposases are enzymes that mediate the movement of DNA within a genome (sometimes called a “jumping gene”). Tagmentation is much more efficient than standard fragmentation and ligation, allowing for more sensitive applications that typically have less DNA input. The tagmentation process has recently been simplified by attaching these transposomes to magnetic beads, thus allowing for fixed amounts of DNA to be captured, whilst undergoing uniform fragmentation and adapter addition. This removes the requirement for each library to be quantified before sequencing, reducing turnaround times and hands-on steps whilst facilitating automation.

Source: Illumina

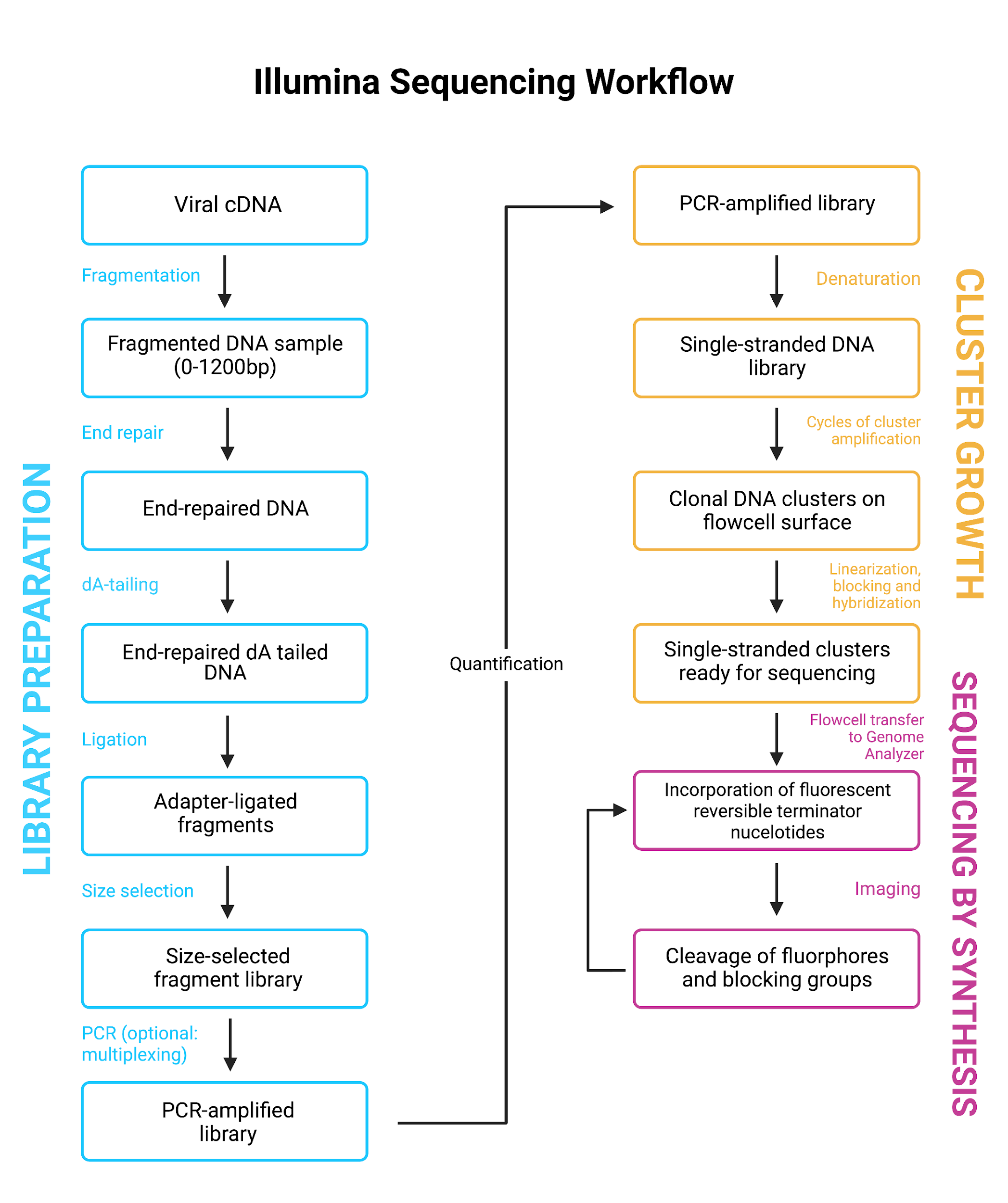

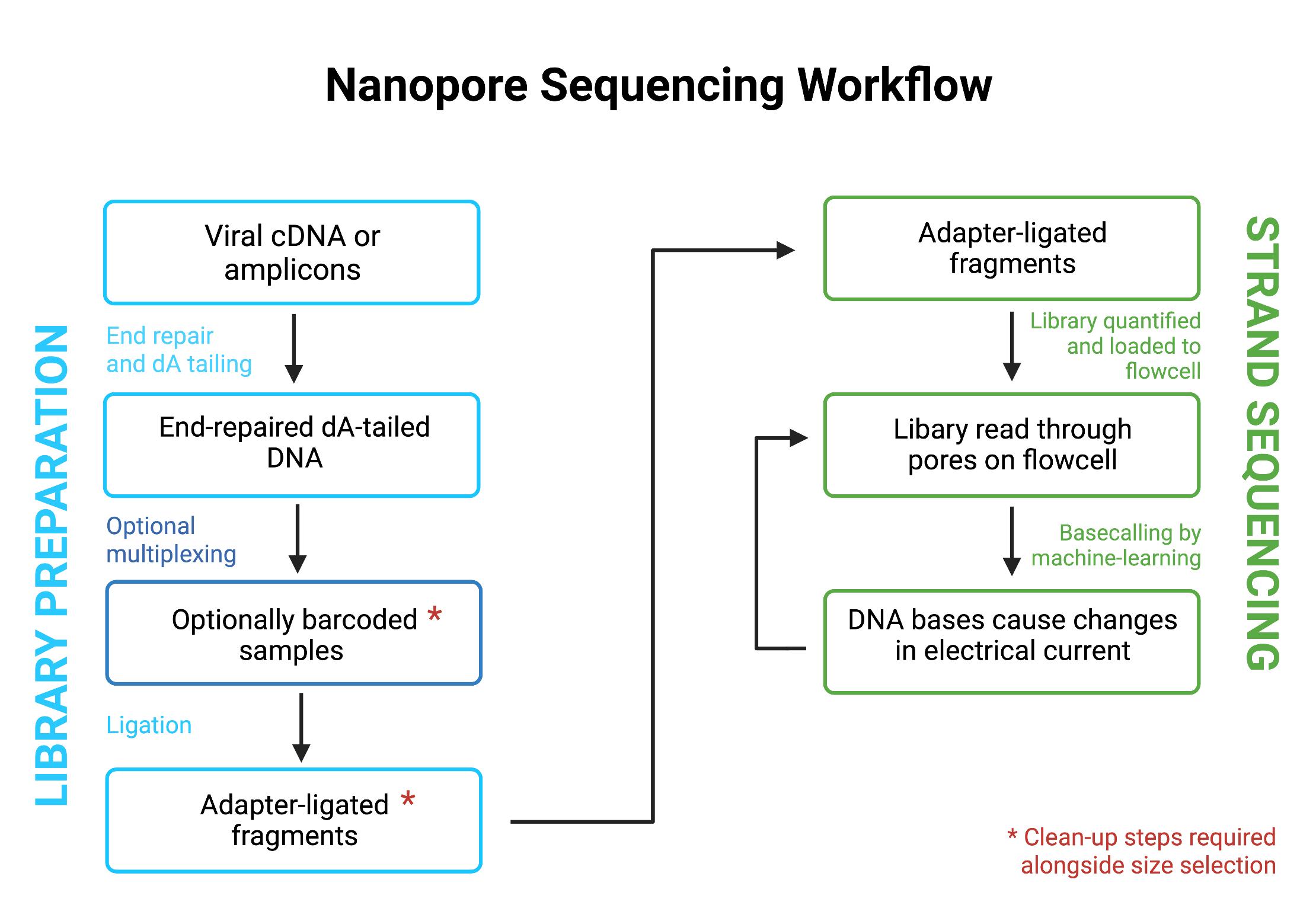

Comparing library preparation methods

Library preparation is the first step of next-generation sequencing (NGS), preparing your samples to allow them to bind to the flow cell and be identified. This article will briefly guide you through standard library preparation for NGS using Illumina and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) sequencing, comparing the differences and similarities between these two methods.

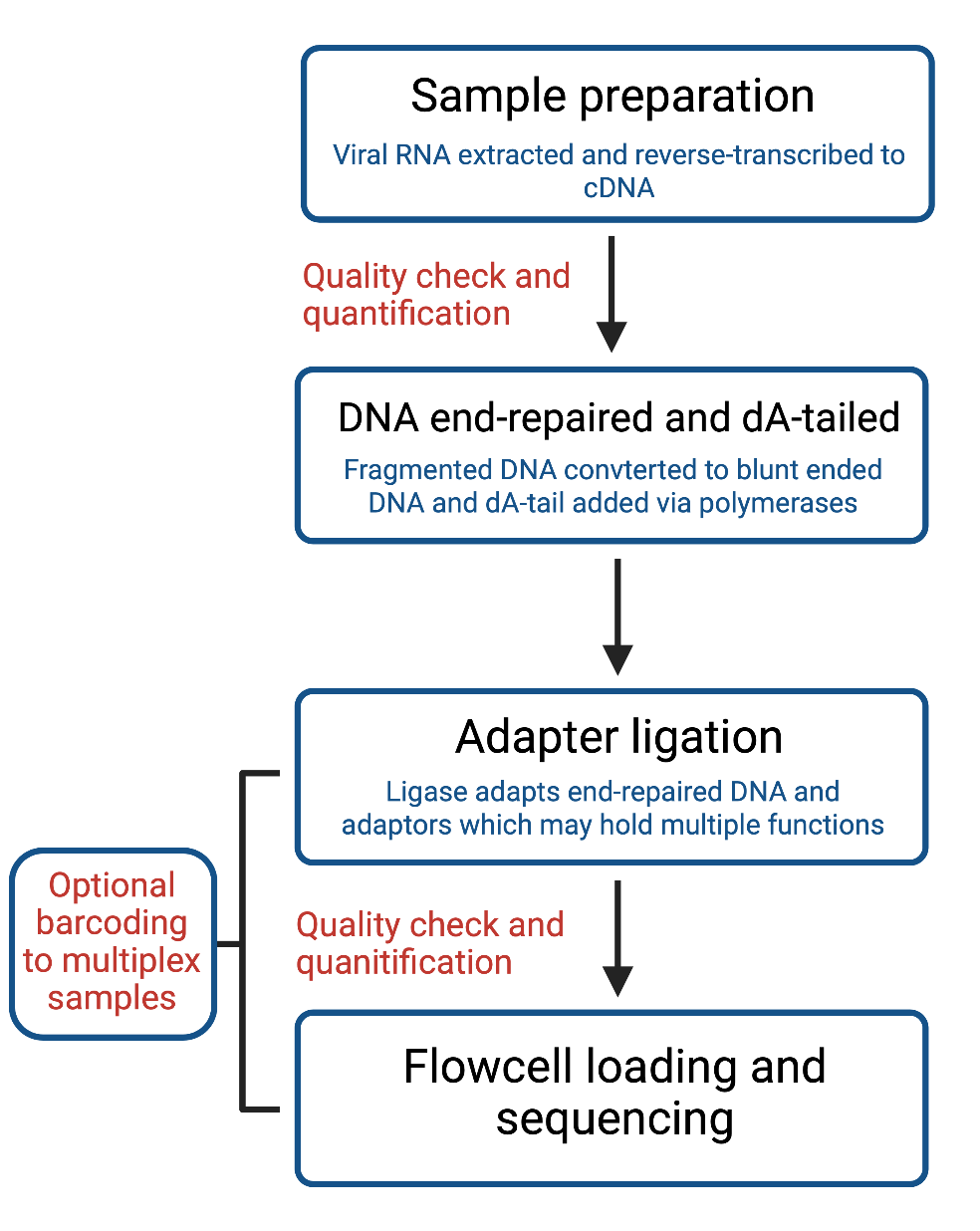

The steps for ligation-based library preparation of any NGS are broadly the same. These consist of the following (Figure 9):

Download Figure 9, 10 and 11 alt-text here

Sample preparation

The first step for COVID-19 library preparation is the reverse transcription of extracted viral RNA to cDNA.

First quality check and quantification

Starting material should always be quality-checked first before beginning the library preparation. This quality check should include quantification to ensure sufficient starting material, and investigating, any signs of contamination as prior clean-up may be required.

End-repair and dA tailing

DNA fragments are end-repaired and dA-tailed. This, therefore, requires converting fragmented DNA to blunt-end DNA containing a 5’-phosphate and 3’-hydroxyl groups via a polymerase, and adding a tailing module to prepare fragments for subsequent ligation steps.

Addition of adapters

A ligase enzyme covalently links the adapter and end-repaired DNA fragments, producing DNA fragments that can be loaded to a flow cell. These adapters serve multiple functions; they predominantly attach the sequences to the flow cell to allow sequencing, and they can also include barcodes to identify samples and permit multiplexing.

Size selection

Another step shared between the protocols is size selection. Although performed at different stages, this step involves including or excluding fragments of DNA most of interest in relation to their size. This is either done using sample purification beads, or can be done simply by gel electrophoresis and band excision.

Second quality check and quantification

A final important step which remains constant in both protocols is quantification and validation of the library prior to flowcell loading, thereby ensuring there is sufficient DNA for sequencing and checks for contamination of controls and samples.

Where Illumina and Nanopore differ is in Illumina’s inability to read long fragments, meaning that Illumina sequencing samples are first fragmented into uniform pieces to make them amenable for sequencing. This is often done by nebulisation, but other methods include sonication, chemical or enzyme-based fragmentation. Generally, this will mean Illumina libraries are subsequently PCR amplified, which also allows for significantly lower DNA input.

Both methodologies allow for the multiplexing of samples, which is regularly used when performing high throughput sequencing of COVID-19 samples. This step is often incorporated with the adapter ligation stage for Illumina library preparation (Figure 10). For ONT, barcoding is a separate step prior to adaptor ligation with separate subsequent clean-up steps required (Figure 11).

Further reading

Library construction for next-generation sequencing: Overviews and challenges

Versatile sequencing library preparation methods for MinION, GridION and PromethION

Illumina: pooling samples and loading cartridges

In this video, you will follow Dr Paola Niola preparing a sequencing library for Illumina methodology.

Libraries prepared using technologies that attach Illumina adaptors to the fragmented DNA are sequenced on Illumina platforms. Libraries made from different samples that have had unique indexes (barcodes) incorporated are pooled together to go onto the same sequencing run. Tip: libraries can be pooled prior to a final clean-up and the pool cleaned, rather than cleaning individual libraries and then pooling. The final pool is quantified by Qubit and the peak size is determined by fragment analysis e.g. TapeStation.

The double-stranded DNA is denatured, diluted to the appropriate loading concentration and pipetted into the cartridge, which is loaded into the sequencer, along with the flow cell and buffer bottle (if applicable).

Nanopore: pooling samples and loading flow cells

Multiplexing and pooling samples

As discussed in the library preparation module, there is an optional step of library preparation which allows for the multiplexing of numerous samples, where DNA fragments from different samples can be pooled and sequenced together. This is regularly used within COVID-19 sequencing, where hundreds of samples need to be sequenced at once, and it makes efficient use of the full capacity of a flow cell.

Multiplexing describes the method by which individual unique “barcode” sequences, often 8-10 nucleotides long, are added to each DNA fragment in a sample so that each read can be identified and sorted during final analysis. In Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) sequencing, this step comes just before adapter ligation, and for Illumina sequencing barcoding is incorporated with adapter ligation. Samples are pooled after barcoding and then loaded into the flow cell (Figure 12)

Source: Illumina. Adapted using Biorender.com.

Download Figure 12 alt-text here

Flow cell loading

Flow cell loading is the process whereby your final library of pooled multiplexed samples is prepped and loaded to the flow cell for sequencing. For ONT sequencing, flow cell loading can be difficult as it involves loading the library directly onto the flow cell, this remains the same for all ONT sequencing platforms. There are extensive ONT resources that carefully describe how this procedure is carried out, the process of flow cell loading for ONT can be seen in the video below.

This video is hosted by a third party

How SARS-CoV-2 has been sequenced around the world

In this video, learn from our global experts what methodologies they have used in their laboratories to sequence SARS-CoV-2.

Comparing manual and automated methodologies

What are the differences between protocols using manual and automated methods? In this video, you will watch the procedures and learn the details of both protocols.

How to avoid contamination

Watch Dr Rachel Williams, Charlotte Williams and Luz Marina Martin Bernal discuss in a video call how to avoid contamination in the sequencing process. How contamination can be observed, what procedures to take in case it happens and how it can be prevented are some of the topics you will learn from them.

Coordinating human resources in a pandemic

Our global experts are back to discuss how they coordinated human resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. They will tell you about teamwork and the challenges of training new members.

How to plan ordering and tracking of reagents

In this video, you will see how to use spreadsheets to automatically calculate ordering quantities by a number of samples.

Legacies of the COVID-19 pandemic

In this video, global experts discuss the lessons they learned during the COVID-19 pandemics: what would they do differently for the next public health emergency? What are the tips and tricks they would like to share with us? Watch the video to find out.