HOW TO MAKE DATA RICHER

@Canva

How different countries tackled the pandemic: an example

NB: this video is in French.

Download the French transcript here

Download the English translation here

In this video, Rodrigue Bakangui, supervisor of the Laboratory of Immunology and Molecular Biology at the Centre de Recherches Médicales de Lambaréné in Gabon, shares how he and his team implemented the SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics and sequencing to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic in Gabon.

Introduction to biobanking

Just like a bank accepts (receives) and safeguards (stores) money owned by other individuals and entities, and then lends (gives out/shares) this money in order to conduct economic activities such as making a profit or simply covering operating expenses (value addition), Biobanks receive and store biological samples and health information in an ethically and legally regulated manner, and shares these samples to researchers who make health sense out of them.

What is a biobank?

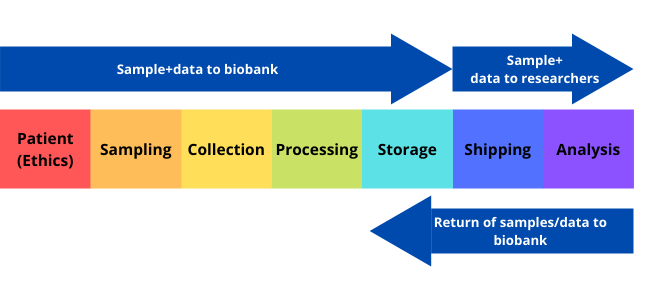

A biobank/biorepository/bioresource is a collection of biological samples and health information. The purpose of a biobank is to process, organise, and maintain various types of biospecimens that are shared for utilisation in both clinical and research-based services (Figure 1).

Click here to enlarge the image

Download Figure 1 alt-text here

Different biobanks collect different types of samples and information. The types of information and samples collected depend on the specific purpose of the biobank. For example, some biobanks are specific to a particular disease, such as cancer. Other biobanks are population-based and contain samples and information from people in a specific population or region. The biobanks have become a crucial resource for medical research since the late 1990s as they support various research such as those in the field of personalised medicine and genomics. In fact, Biobanks are listed among the 10 big ideas changing the world by Times Magazine. Biobanks allow researchers to access data that represents a large number of people. The biospecimens and data acquired can be used by multiple researchers for cross-purpose research studies.

Biospecimens

Biospecimen types that are available include organ tissue, blood, saliva, urine, skin cells, and other tissues or fluids taken from the body. The samples are maintained in appropriate condition to prevent deterioration and are protected from accidental and intentional damage. The sample is registered in the computer-based system. The physical location of the specific sample is also noted to enable the specimen to be easily located when required. Samples are de-identified to ensure donor privacy and allow the blinding of researchers to the analysis. Room temperature storage may be used in some cases as it helps with cost efficiency and avoids issues such as freezer failure.

Ethics

Biobanks can only store and share samples if they follow the required ethical guidelines. Some ethical issues regarding biobanking are the ownership of samples, ownership of derived data, the right to privacy for donors, the extent of donor consent, and the extent to which the donor can share regarding the return of research results.

How does a biobank make performing research easier?

The biobank serves as a library for researchers. Therefore, the time and resources needed to recruit new participants for each research study are greatly reduced because samples and corresponding medical information are available in one place. By making sample collection and patient recruitment more efficient, better studies can be performed in a timely fashion.

Walking through a biobank

In this video, Gideon Nsubuga walks us through the Integrated Biorepository facility of H3Africa at Makerere University, Uganda and shows that biobanking is a lot more than a freezer farm.

What is metadata?

Metadata is any additional information that can be collected on a sample that is being sequenced. For clinical samples, it is mostly information about the patient, testing, and sample types. This information helps us discover links between the sequencing data that would not otherwise be possible e.g. in a set of suspected hospital outbreak samples, metadata like time of sample collection and ward location of the patient where the sample was collected can help confirm or refute related outbreak clusters found in sequencing data.

For instance, COG-UK collected a large number of fields relating to each sample. The metadata collected could be broadly divided into the following categories.

Biosamples – Metadata fields collected in this category were mostly related to the actual patient the sample was collected from e.g. sample collection dates, location, age, sex, admitted hospital etc.

Metrics – Metadata fields in this category describe the quality of the samples. This comprised mostly of the ct value, the target gene and the platform used to assess the ct.

Library – This category mostly captured information on the library preparation methods for the genomic material to be sequenced like primers types, library kits, library sources etc.

Sequencing – This category captured information on final sequencing and data analytics like the sequencing technology and machine used along with bioinformatics pipelines for downstream data analysis.

During the COG-UK sequencing project, metadata used was anonymised data about a single sample. This information was uploaded by the sequencing centre to a database known as MAJORA which would link up the information with the sequencing data anonymously. Both open-source data could then be displayed such as ‘date of the sample collection’ and then restricted data such as ‘laboratory ID’ could also be uploaded at the same time.

By using metadata, it helps to let us identify if there are metadata subjects that have provided different patterns such as care homes or hospital environments. It helps us understand epidemiological patterns such as certain variants emerging and to determine if samples associated with the same outbreak show similar sequencing results. Metadata is crucial for creating policy or knowing where increased surveillance or testing is required.

Collecting such a large number of metadata fields per sample is always challenging and time-consuming. One key challenge is maintaining standards for each input field as various locations globally have slightly different ways of recording the same data. There is a push in international communities to standardise fields, especially now for SARS-CoV-2. Global sequence databases like GISAID have a standardised format in which data is recorded. There is work happening at PHA4GE (Public Health Alliance for Genomic Epidemiology) and you can read more about that on the GitHub resources page. The other main issue of collecting patient data is the storage of sensitive data as there are fields collected that are considered PII (Personally Identifiable Information). One should be aware while collecting the data of what fields are considered PII and secure the data appropriately in accordance with the data protection rules in that country.

Types of metadata

The metadata can be divided into three tiers:

Tier 1 corresponds to essential core metadata,

including the following label:

- Sample identification number

- Sample type can be labelled as sputum, blood, serum, saliva, stool,

nasopharyngeal swab and wastewater

- Sample collection date is a field that can potentially be used to

inform on introductions and evolutionary rates

- Country of the collection can be used to inform on introductions of a

virus, transmission routes and can be used in BEASTanalysis (Bayesian

Evolutionary Analysis Sampling Tree)

- State/province of collection

- Originating diagnostic lab, which is the laboratory where the clinical

specimen or virus isolate was first obtained

- Sequencing submitting lab is the lab where the sequence data was

generated and this metadata can be used to assess sequencing

capacity

- Sampling method, where samples can be labelled as routine surveillance

or focused sampling, representative or targeted sampling

- Host can correspond to human samples or a specific animal, environment

or unknown, for example

Tier 2 corresponds to descriptive metadata,

including the following labels:

- Age, sex (including for example male, female, other and unknown) and

race/ethnicity (considering individual collection laws) can be used to

assess risk factors

- Health worker status can be classified as yes, no or unknown and it’s

also important to understand risk factors but also transmission

routes

- Travel history should include locations(s) and timing and it’s

important not only to understand introductions of the virus but also

transmission routes

Tier 3 corresponds to metadata for characterisation,

including the following labels:

- RT-PCR assay used (if any)

- RT-PCR Ct value (if any)

- Symptomatic, for example, yes, no, unknown, is an important label to

perform severity analysis

- Vaccination status for humans should include the date of vaccination,

including for doses one and two, vaccine type, source of information

such as documented evidence (vaccine register our vaccine card) versus

recall, and can be used in vaccine failure studies

- Date of symptom onset can be used to assess the delay between onset

and sequence submission

- Hospitalisation status for example hospitalised never hospitalised and

unknown can be used for severity analysis studies

- Admission to the intensive care unit, mechanical ventilation outcome

(deceased or recovered) can be used in severity analysis studies

- Past history of SARS-CoV-2 to infection and dates are important to

assess re-infection risk

- Therapeutics received, include COVID-19 specific therapeutics and this

type of metadata can inform therapeutic failure studies

- Location of exposure, and link to known cluster/outbreaks can inform

cluster outbreak analysis and transmission routes and transmission

routes

- Contact with known animal reservoirs is relevant to support

transmission routes studies

- Comorbidities known to increase the severity of COVID-19 can be used

in studies to determine risk factors

More information can also be found at the COG-UK Inbound Operations Repository and COG-UK Docs repository

Additionally, the WHO suggested a table for collecting metadata. The items are colour-coded according to their importance and the red items are essential.

Download WHO’s metadata table here

Data collection tools

What is Data Collection?

Data collection is the methodical process of gathering and analyzing specific information to provide solutions to relevant questions and evaluate the results. It focuses on finding out all there is to a particular subject matter.

What is a Data Collection Tool?

A data collection tool is an instrument used to collect data intended to answer a particular question(s), such as a paper-based or a computer system. The underlying need for data collection is to capture quality data that seeks to answer questions that have been posted. The choice of the tool to use is mainly determined by the likelihood of errors, cost, and time.

The Different Data Collection Tools – During the Pandemic?

It is useful to ensure that quality data is collected so that you can draw inferences and make informed decisions on what is factual. In relation to sampling and testing during the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals, public and private institutions participating in the COVID-19 testing or surveillance have deployed different tools for data collection of patients’ information, samples and test results information around the pandemic.

1) Laboratory Investigation Forms (LIFs):

When the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, the ministry of health in Uganda, together with the different laboratories involved in the sample collection and testing developed a standard Laboratory Investigation Form for enrolling and documenting all the important information about the COVID-19 suspected patients and samples. This form would be printed into booklets and distributed across the country to the different COVID-19 collection and testing facilities. Similar forms, both paper and online are used globally to record critical patient information. Challenges arise from the ability to quickly and accurately collate and combine this data at scale for public health benefit.

2) Common Online Survey Tools:

Google Forms: This is a free survey administration software included as part of the free, web-based Google Docs Editors suite offered by Google. It helps you to easily create and share polished surveys and forms to respondents from which you can analyze their responses.

Microsoft form: An online survey creator, part of Office 365 by Microsoft. It allows users to create surveys and quizzes, and the data from respondents can be exported to Microsoft Excel for further analysis.

Doodle forms: This is a free online tool that allows users to create questionnaires to gather people’s opinions.

Emails: You can use emails, webmail or mailing lists to send out questions or questionnaires for which you receive feedback from the respondents.

Social Media: During the CoVID-19 pandemic, many organisations and individuals used social media such Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter to collect information from users about the pandemic.

3) Common Online Data Collection Tools:

Open Data Kit (ODK): ODK is open-source software for collecting, managing and using data in resource-constrained environments. It allows for offline data collection with mobile devices in remote areas and the submission of the data to the server can be performed when internet connectivity on the device is available.

RedCap: A web application for building and managing online surveys and designing clinical and translational research databases. It provides for the export of the data into other applications for further analysis.

Kobotoolbox: It is a free and open-source software suite of tools for field data collection for use in challenging environments. It provides simple, robust and powerful tools for data collection and analysis.

Custom software applications. Customised software is software that is specially developed for a specific organisation or user. In circumstances where the available tools cannot meet your needs, one can develop their own software application for their data collection needs.

Public databases benefit epidemiology

For researchers, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the most significant mission has been to produce valuable data regarding infection and transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Equally important has been to share such data quickly and unreservedly to be looked at by others in real time.

Such data sharing has enabled connectivity between researchers and policymakers and between regions across the world, helping to build the foundations of a global surveillance programme. Data sharing has become a valuable way to evaluate (and sometimes prevent) the effect of incoming variants into different latitudes. A relevant example of efficient data production and data sharing, includes the initial identification of the highly contagious Omicron variant in South Africa in November 2021. As a consequence, many countries were rapidly aware of this variant and initiated studies on its possible effect. Tailored PCR methods were developed or adapted to detect this variant (without nucleotide sequencing), reducing the costs of its detection. This is an extraordinary example of how high-quality research can inform global public health.

At the beginning of the pandemic, relevant information was shared on social media or in specialised blogs. Of outstanding importance was the discussion forum Virological where the first whole SARS-CoV-2 genome was shared by Chinese-Australian scientists, and later was the niche to discuss relevant epidemiological and genomic information. For instance, many of the variants of interest or concern were first described on this blog (like alfa, gamma, lambda, mu, etc.). The blogging community has also discussed: the possible SARS-CoV-2 origin, whole-genome sequencing protocols, variants classification, and nomenclature.

Early in 2020, not many specialised databases were available to share large quantities of genomic data. For that reason, the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nucleotide database in the USA and Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Data, known as GISAID, gathered data, curated it and shared it openly. GISAID became the preferred database to share SARS-CoV-2 genomes worldwide, holding sequencing data for a staggering amount of 9.5 million SARS-CoV-2 genomes by March 2022.

Epidemiological databases created to share and visualise COVID-19 information Databases like Our World in Data are reliable information sources used even by the World Health Organization and regional health organisations. This database collects information from at least 57 different sources and provides trustworthy indicators such as infections, hospitalisations, officially reported deaths, and excess deaths. This is especially helpful in developing countries that do not possess open databases or cannot openly share most of their information.

Research findings databases became remarkably popular during the pandemic, for example, preprints servers like bioRxiv and medRxiv where non-peer-reviewed studies are shared with preliminary or complete results. Minimum requisites must be fulfilled to publish on these databases. Whilst lots of information produced was derived from non-verified or even fraudulent data which open scrutiny could not entirely confirm; nevertheless, it changed scientific information access forever. Canonical peer-review journals are still the most reliable approach to obtaining reliable research data. Additionally, most publishers have their published papers directly available or through open-source libraries such as PMC or Pubmed. Finally, wet lab, statistics, and bioinformatics protocols have been also shared in public databases such as GitHub. Such databases provide quick updates on protocols, comments, and adapted pipelines that developers directly share.

Ensuring sample/data consent and ownership

Download the presentation slides here

In this lecture Malebo Malope from Stellenbosch University, South Africa reviews informed consent and discusses who owns the data.

Please visit the POPI Act website to learn more about the Protection of Personal Information Act from South Africa.

Data enrichment benefits to epidemiology

The process of appending or otherwise augmenting gathered data with relevant context gained from extra sources is known as data enrichment. It’s done by appending various attributes and values from different data sets to one or more data sets.

Allows you to collect useful data

Enriched data describes important data that is relevant to the problem and scenario at hand and that may be shared across stakeholders such as epidemiologists, healthcare workers, researchers, and other shareholders. This might include data such as travel history, vaccination status or prior infection data. Enriched data allows you to address more than one research question at a time.

Enhances data quality and accuracy

Good data enrichment techniques validate the information and ensure that the data is current. Allows for extensive data collection by linking data from numerous sources, as well as improved validation of exposures and research endpoints. This may involve combining different research databases, hospital and community data, health records and patient self-reports.

It saves time

You’d think that adding more data would take longer. Data enrichment, on the other hand, reduces the amount of time and effort required to complete a task by allowing for AI-assisted automation. Using historical medical records as a baseline can shorten multi-year study timelines. Due to the link to continuous medical records data, also reduces timelines for follow-up studies

Provides Deeper insights

Provides a more solid evidence base for addressing specific research goals. It also allows for analysis to be carried out in parallel with studies based on continuous medical records data. The addition of patient-reported data, also allows researchers to generate more patient-centred insights.

Additionally, through existing data sources, insights can be gained earlier, informing feasibility, generating new research questions, and providing information on the path to diagnosis, disease characteristics, or treatment patterns. Furthermore, clinicians who do not have robust research infrastructures can participate in studies, resulting in more representative populations than those seen at research-savvy centres. Because existing clinical data alone are frequently insufficient to fully establish the value of treatment intervention, the ability of enriched studies to supplement existing data with patient-reported information opens up new avenues for greater impact.

Benefits and challenges of integrating clinical data

In this video, Prof Emma Thomson from the University of Glasgow explains the importance and implications of integrating sequencing and clinical data.

You can learn more about the Safe Haven System that Emma mentioned on the NHS Scotland website

Practical challenges: setting up a laboratory during lockdown

In this roundtable discussion, Dr Sharon Glaysher, Dr Sam Robson and Angie Beckett from the University of Portsmouth talk about their experiences setting up a sequencing laboratory on the verge of a national lockdown.

De-centralising genomic surveillance

To address the pressing challenge of centralised genomic surveillance, the Philippines Department of Health (DOH) with its established surveillance network was utilized to leverage the crafting of additional genomic surveillance for SARS-COV-2 led by the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM) in collaboration with various Sub-national Laboratories (SNLs); the Epidemiology Bureau (DOH-EB); the Regional Epidemiology and Surveillance Units (RESUs) and its surveillance units within the DOH; and strong support from the University of Glasgow (UOG) with funding from the UKRI GECO-COMP. This project dubbed the GECO PH Project is deemed to be a landmark catalyst to empower local laboratories to perform their own genomic surveillance using state-of-the-art real-time Nanopore whole genome sequencing technology (e.g. MinION, GridION). This initiative has boosted the sequencing capacity of the Philippines for genomic surveillance, particularly for COVID-19.

The Genomic Epidemiology of COVID in the Philippines (GECO PH) project has operationalized genomic surveillance and informed responses across the Philippines to embed large-scale real-time sequencing capacity at the national reference laboratory (RITM) and builds local sequencing capacity at (Sub-national Laboratories) SNLs for national, regional, and local-scale responses in the Philippines. The research will further enable the evaluation of control measures across settings, from infection controls to prevent hospital-acquired infections, lockdowns to interrupt community transmission, and quarantining and movement restrictions to contain introductions, whilst increasing our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 transmission and control.

Ensuring sample and data ownership

Due to the intricate natures, functions, and relationships of each stakeholder within the healthcare system in the Philippines, the RITM as the national reference laboratory for emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases of the Department of Health (DOH), forged agreements with the SNLs, Epidemiology Bureau (DOH-EB), and the University of Glasgow (UOG) to formalize and ensure the roles and responsibilities of each stakeholder are clear, distinct, and avoid overlap with each other. Embedded within the agreements is the participation of the SNLs in a consortium which facilitates the sharing and cooperation within the context of research and investigation of SARS-CoV-2 sequences and associated data. Moreover, it underpins the upholding of scientific etiquette, by acknowledging the originating laboratories providing the specimens, and the submitting laboratories generating sequence and other metadata, ensuring fair exploitation of results derived from the data, and promoting collaboration among researchers on the basis of open sharing of data and respect for all rights and interests.

To guarantee the success of the GECO PH surveillance through the consortium, the project undertook the following key steps and activities:

Ethical Clearance

The research project obtained approval from the Single Joint Research Ethics Board of the DOH and various local ethical boards of the RITM and SNLs, a vital part of the framework of crafting the biosurveillance of SARS-COV-2 in the country.

Advocacy

Advocacy is critical to the roll-out of the surveillance project and its sustainability and future integration into the surveillance program of the DOH, the principal health agency in the Philippines responsible for the regulation of various healthcare providers including the SNLs and DOH-EB for the provision of health services, particularly in the ongoing pandemic. A policy issuance from DOH ensured support for the capacity building of RITM and more particularly the SNLs to carry out their own sequencing activities. Moreover, a series of meaningful meetings were conducted to formalize the consortium’s objectives and goals.

Consequently, a laboratory needs assessment was conducted to identify gaps, propose solutions and ensure the readiness of the SNLs for rapid sequencing. The needs assessment includes evaluation of facilities (space for workstation and equipment, Wi-Fi access, sample storage, etc.), logistics (supplies and sample transport), biosafety (PPEs, disinfection/sterilization procedures, waste disposal, etc.), equipment, staff (knowledge and skills), metadata (electronic and paper records, kinds of data collected, etc.), and policy environment for genomic research and surveillance.

Coordination

To facilitate close coordination within the consortium, regular meetings using various social media platforms such as Viber chat groups and Slack channels are employed for rapid updates, planning, queries and dissemination of information and guidance.

Training

Capacity building to perform rapid sequencing hallmarks the crafting of the consortium. There is a great fervour among the SNLs to acquire knowledge, skills and technology to sequence the genome of pathogens particularly SARS-COV-2. Briefly, the training comprised lectures and demonstrations videos; and practical/hands-on sessions. Practical sessions include primarily cDNA preparation, multiplex PCR, library preparation, sequencing, data retrieval from Mk1C and basic bioinformatics and RedCAP exercises.