Glossary

- Adaptors: a short chemically synthesised single or

double-strand DNA (oligonucleotide) used in some sequencing

methodologies that allow the addition of a DNA barcode or other

oligonucleotides downstream of an unknown or amplified DNA strand.

- Amplicon: a DNA fragment that has been amplified

using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or a method that results in the

generation of multiple copies of that fragment.

- A-tailing: an enzymatic reaction to add a sequence

of adenines at the 3’-terminus of a DNA fragment for sequencing

purposes.

- Barcoding: addition of a tag of known DNA sequence

(barcode, also called index) to an amplified DNA strand that permits

sequencing multiple samples in parallel, and stratifying sample data

informatically post/during sequencing.

- cDNA: complementary DNA, a DNA molecule synthesised

from an RNA molecule.

- Consensus sequence: a sequence of DNA, RNA or

protein generated from a set of aligned sequences. It is calculated

based on the most frequent nucleic acids or residues in each position of

the alignment.

- COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019.

- DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid, which is an information

molecule forming the “base code” for a living organism.

- Enzyme: a protein able to catalyse, i.e. accelerate

chemical reactions.

- Library: in the sequencing context is a pool of DNA

fragments attached to adaptors and/or other oligonucleotides used during

sequencing preparation procedures.

- ONT: Oxford Nanopore Technologies, a sequencing

technology company. Their sequencing platform is also referred to as

ONT.

- PCR: Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a

laboratory technique for rapidly making (amplifying) millions to

billions of copies of a given section of DNA, which may then be analysed

further.

- Primer: a short chain of oligonucleotides used to

target and ‘prime’ the initiation of DNA replication.

- Protein translation: is the process of synthesising

proteins from a transcript.

- NGS: next-generation sequencing, a high throughput

sequencing methodology.

- Nucleotides: the individual subunits that form DNA

and RNA molecules.

- RNA: ribonucleic acid, an information molecule, can

be the “base code” for viruses.

- SARS-CoV-2: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

Coronavirus 2.

- SNP: single-nucleotide polymorphism is a nucleotide

substitution in a specific position of the genome. It is identified when

compared to a reference sequence.

- Transcription: is the process of copying a segment

of DNA into RNA.

- Tagmentation: is the initial step in library

preparation where unfragmented DNA is cleaved and tagged for

analysis.

- Trimming: in bioinformatics, it is the process of

removing the ends of the reads, leaving only a region of high-quality

bases and those relating to the sample, not the sequencing chemistry or

DNA barcoding.

- Viral replication: is the mechanism in how viruses

propagate during the infection cycle, it is the process of virus

multiplication.

- Viral genome variant: a virus that has one or more

mutations in its genome.

- Whole-genome sequencing (WGS): is the method of determining the entirety, or almost the entirety, of an organism’s genomic DNA sequence all at once. This entails sequencing all of an organism’s chromosomal DNA, and DNA found in mitochondria and, in plants, chloroplasts.

Learning more about SARS-CoV-2 genome

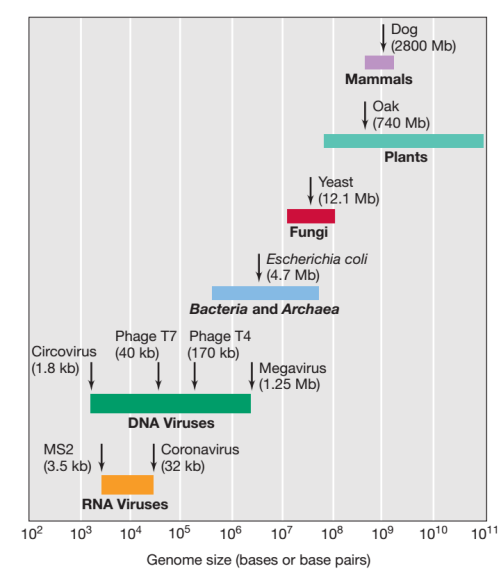

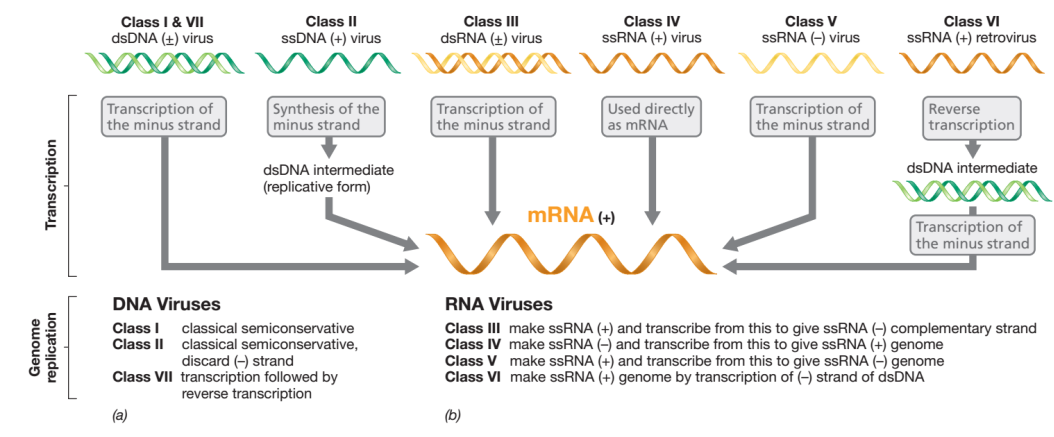

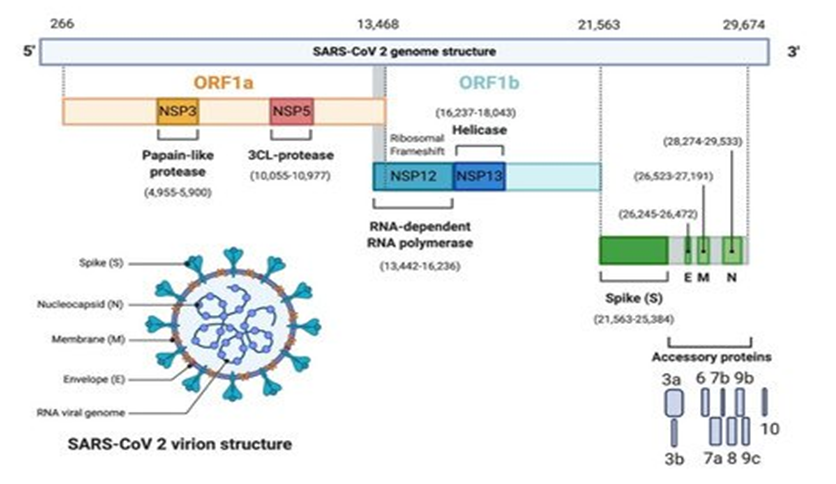

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are a group of enveloped viruses that have a positive single-stranded RNA genome.

The genome size ranges between 27–32 Kbp, and is one of the largest known RNA viruses. The genomic structure of CoVs contains at least six open reading frames (ORFs). The genome encodes two large genes ORF1a (yellow), ORF1b (blue), which encode 16 non-structural proteins (NSP1– NSP16), shown in Figure 3. These NSPs are processed to form a replication–transcription complex (RTC) that is involved in genome transcription and replication. For example, NSP3 and NSP5 encode for Papain-like protease (PLP) and 3CL-protease, respectively. Both proteins function in polypeptides cleaving and block the host’s innate immune response. NSP12 encodes for RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). NSP15 encodes for RNA helicase. The structural genes encode the structural proteins, spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N), highlighted in green. The accessory proteins (shades of grey) are unique to SARS-CoV-2 in terms of number, genomic organisation, sequence, and function.

Source: Frontiers

Download Figure 3 alt-text here

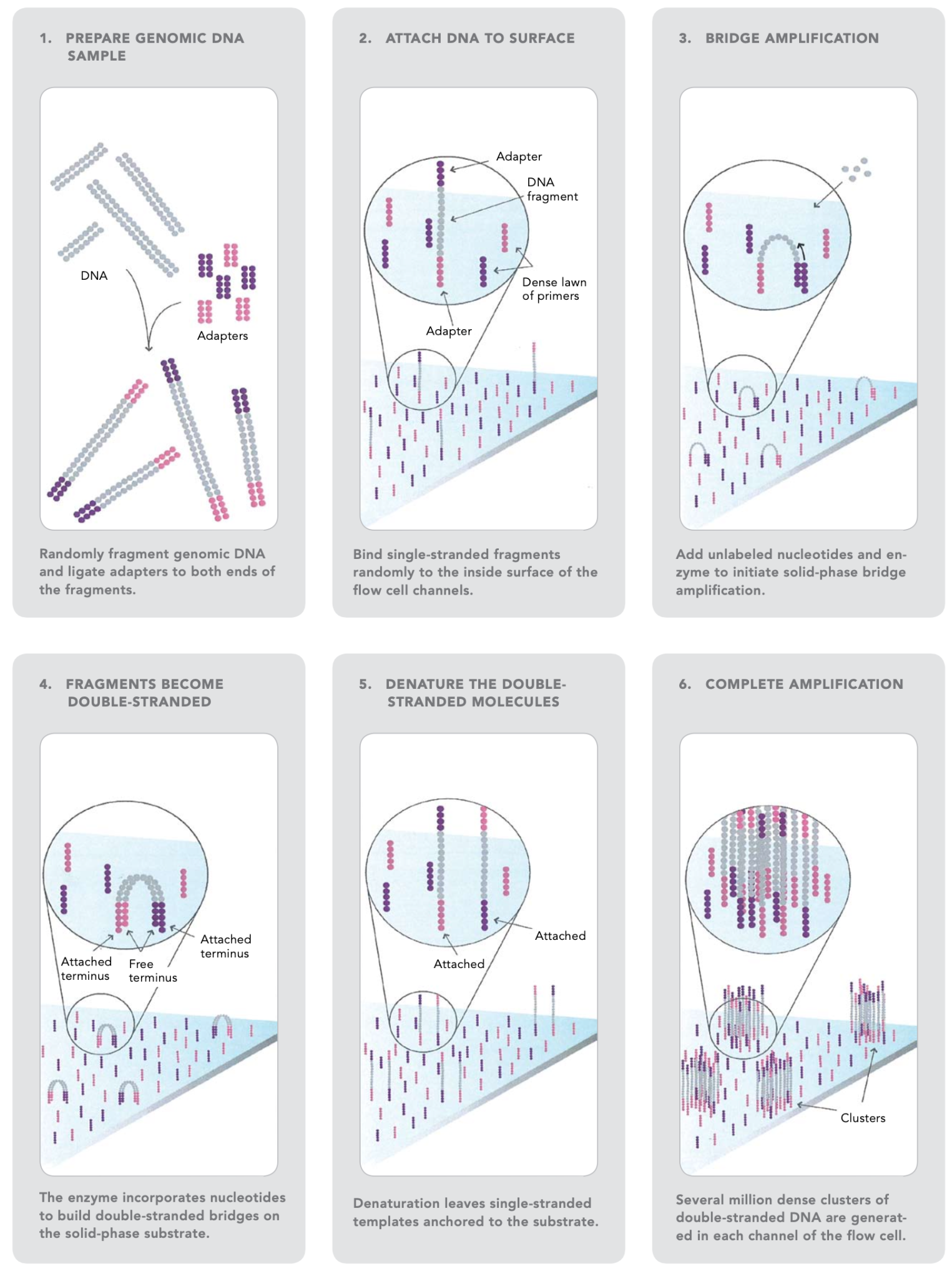

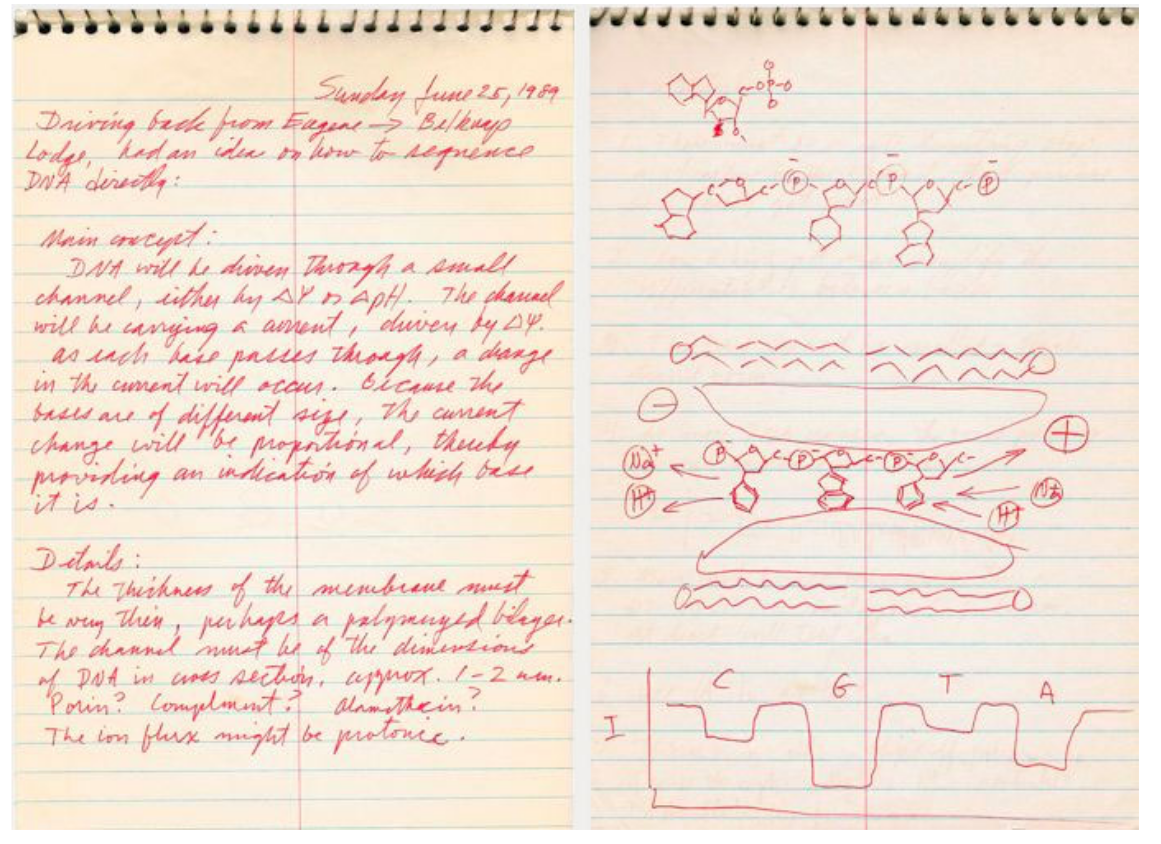

How to sequence using Illumina technology

Illumina dye sequencing is a molecular technique for determining the base pair sequence in DNA.

It was developed by Cambridge University’s Shankar Balasubramanian and David Klenerman, who later founded Solexa, which was acquired by Illumina. This method of sequencing is based on a technique known as “bridge amplification,” in which DNA molecules of approximately 500 bp are used as substrates for repeated amplification synthesis reactions on a solid support (i.e., the flow cell) containing oligonucleotide sequences complementary to a ligated adapter. The oligonucleotides on the surface are arranged in such a way that after several rounds of replication, the DNA forms clonal “clusters” of around 1000 copies of each oligonucleotide fragment. Millions of parallel cluster reactions can be accommodated on the flow cell. During the synthesis procedure, patented modified nucleotides corresponding to each of the four bases are added and then detected using a different fluorescent label. The nucleotides also function as reaction terminators, which are unblocked after detection to enable the next round of synthesis. This sequence of reactions is then repeated 300 times or more.

The sequencing workflow consists of four major steps (sample preparation, cluster formation, sequencing, and data analysis), which can be further subdivided as follows (Figures 4 and 5):

Source: Illumina Inc.

Download Figure 4 and 5 alt-text here

The first step is to fragment the DNA into more manageable 200-600 base pair segments.

Short DNA sequences known as adaptors are ligated to the DNA fragments. The adaptor-ligated DNA fragments are converted into single-stranded forms using sodium hydroxide.

The DNA libraries are loaded onto the flow cell. The adaptor DNA binds to complementary sequences on the flow cell’s surface, and unbound DNA is washed away.

The DNA bound to the flow cell is then replicated to generate small clusters of DNA.

When these molecules are sequenced, they emit a signal powerful enough to be detected by a camera.

Unlabeled nucleotides and DNA polymerase are then introduced to the flow cell to extend and link the DNA strands. This results in the formation of ‘bridges’ of double-stranded DNA between the primers on the flow cell surface.

Source: Illumina Inc.

Using heat, the double-stranded DNA is broken down into single-stranded DNA, resulting in many million dense clusters of identical DNA sequences.

Primers and fluorescently labelled terminators (a type of nucleotide base that stops DNA synthesis) are added to the flow cell.

The primer binds to the DNA that is being sequenced.

After binding to the primer, the DNA polymerase adds the first fluorescently-labelled terminator to the newly synthesised DNA strand. Once a base is added to the strand of DNA, no additional bases can be added until the terminator base is removed. Lasers are used to activate the fluorescent label on the nucleotide base of the flow cell. A camera detects the fluorescence and records it on a computer. Each terminator base (A, C, G, and T) emits a distinct fluorescent signal.

The fluorescently-labelled terminator group is then removed from the first base, and the second fluorescently-labelled terminator base is inserted next to it. This cycle is repeated until millions of clusters have been sequenced.

Base-by-base analysis of the DNA fragment occurs during sequencing, making it very accurate. The resulting sequence can then be compared to a reference sequence to look for matches or differences in the sequenced DNA.

Various methodologies are supported by Illumina sequencing, including whole-genome, exome, and targeted sequencing, metagenomics; RNA-seq; CHIP-seq; and methylome approaches. Throughput varies for each sequencer model, including the MiniSeq, MiSeq, NextSeq, HiSeq, and NovaSeq lines. The MiniSeq can store 7.5 Gb of data and generate 25 million reads per run in segments of 2 x 150bp reads. The MiSeq has a capacity of 15 Gb and can generate 2 x 300bp reads. The NextSeq can provide 120Gb with 400 million reads at a read length of 2 x 150bp. Details about each instrument and its capabilities in relation to specific sequencing projects may be found on Illumina’s website.

This video is hosted by a third party

Why was Nanopore sequencing used in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic?

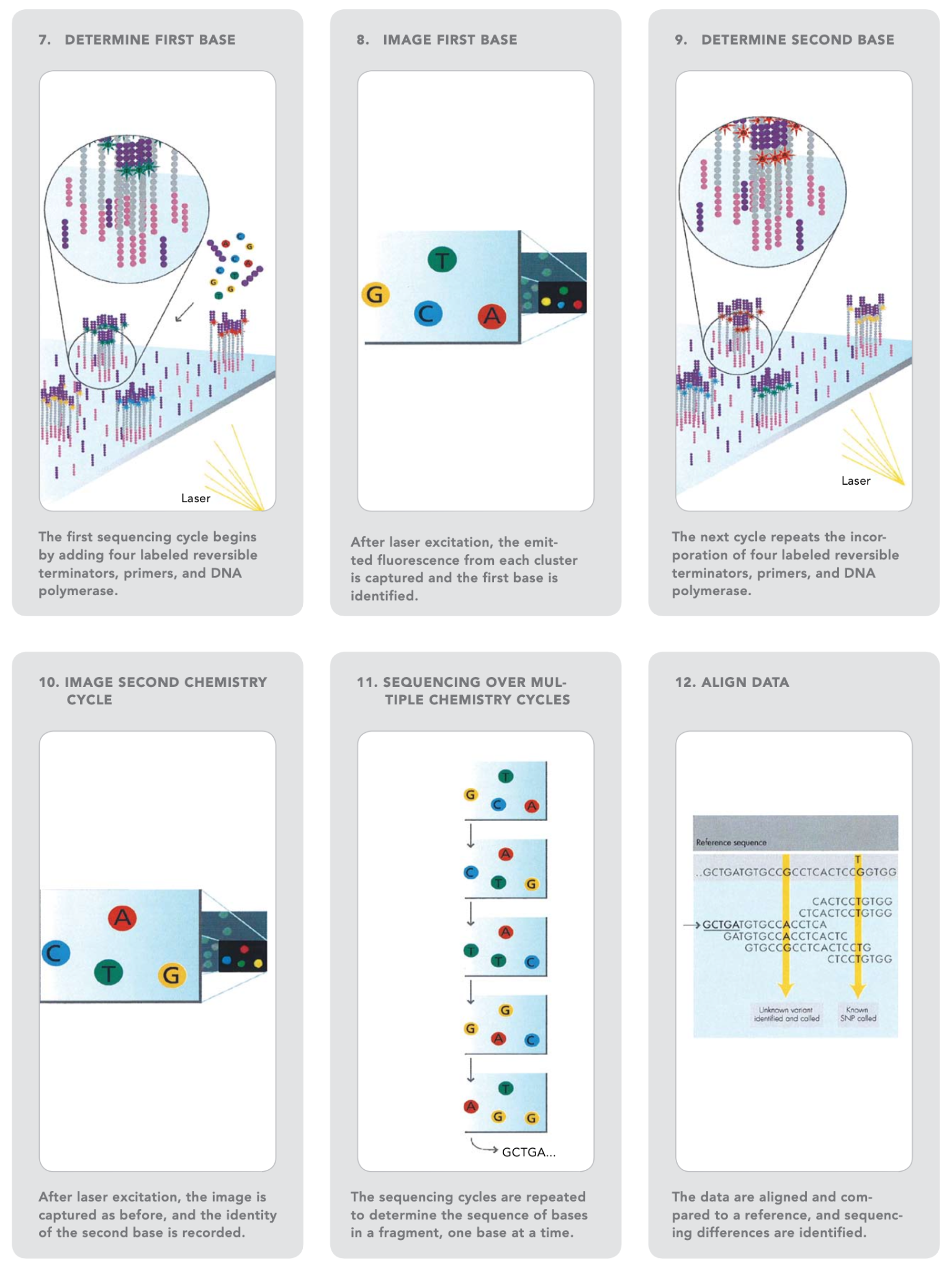

How did Nanopore Sequencing start?

The concept of using a protein nanopore as a method to read DNA was first realised in 1989 by Professor David Deamer (Figure 6). Since his original design, the concept of individual nucleic acids passing through a nanopore which was embedded in a bi-lipid membrane was first put into practice, and patented, in 1998.

Source Nature Biotechnology

Download Figure 6, 7 and 8 alt-text here

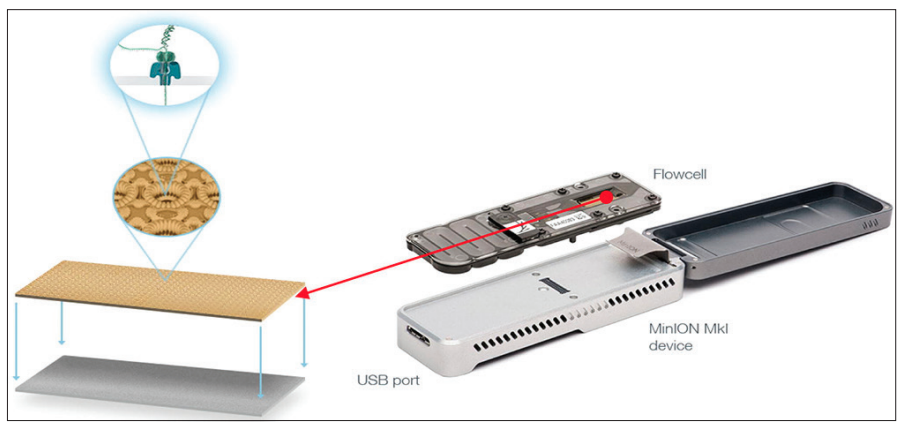

The commercialisation of nanopore sequencing, however, wouldn’t become available until 2012 with the release of the MinION device. Later variations, such as the PromethION in 2018, were developed and allowed the parallel sequencing of multiple libraries to be visualised for the first time. Equipped across 48 flow cells, the PromethION can process 7 Tb of sequence data in a single run.

How does Nanopore sequencing work?

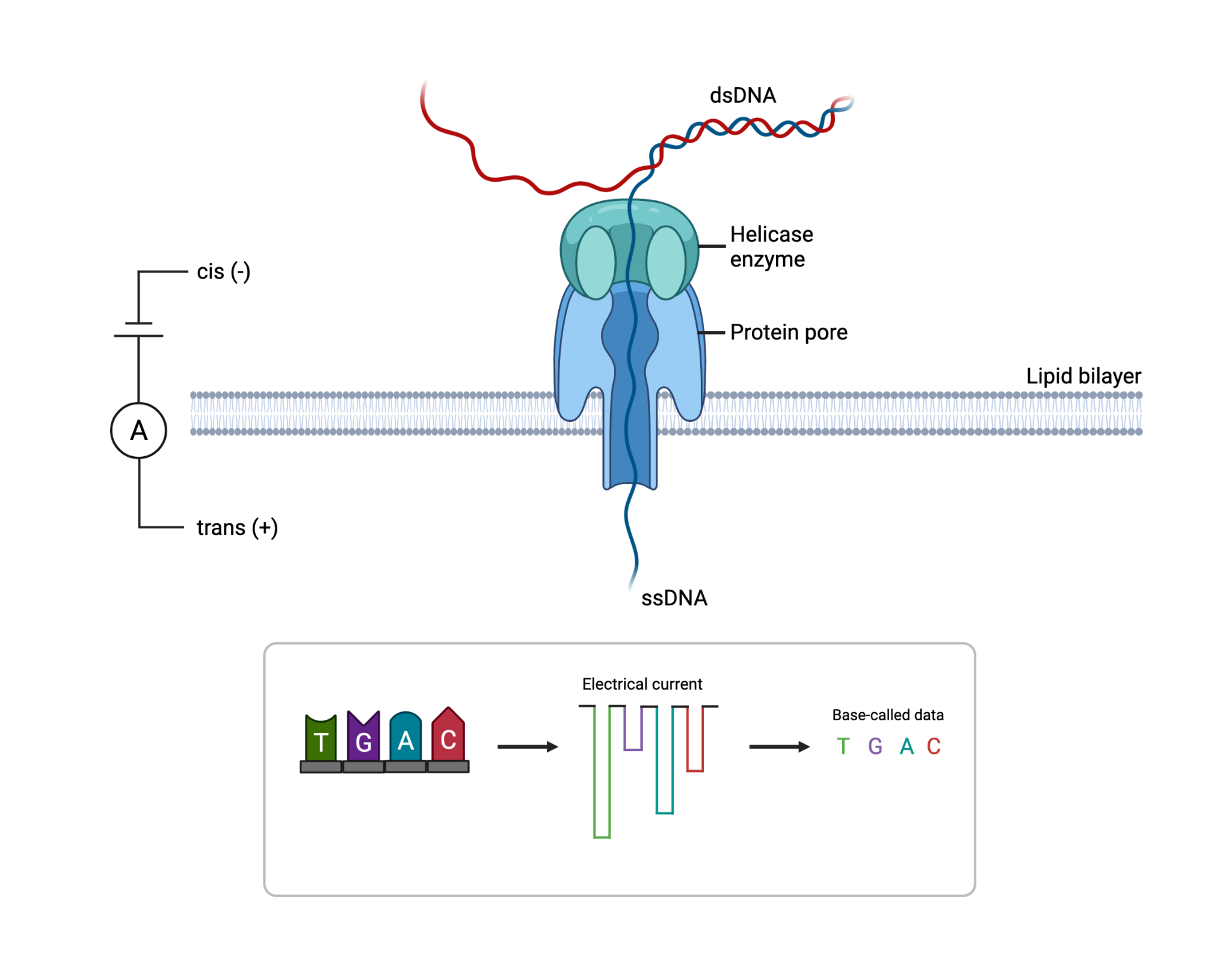

The flow cell contains a synthetic electro-resistant membrane across a small surface and is embedded with up to 2000 individual holes known as nanopores. Each nanopore is a nanometre across and contains a helicase enzyme to unwind the double-stranded DNA into its single-strand components upon entry. The nanopore (Figures 7 and 8) acts as a biological vessel that transports the DNA from one side of the flow cell to the other. The DNA or RNA that passes through the narrow sensor of the reader protein is read and base called. When working at optimum capabilities, the nanopores can produce raw data reads of up to 400 base pairs a second resulting in large quantities of data being produced.

Source: Surgical Neurology International

Why was Nanopore sequencing used in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic?

Conventional sequencing technologies have a high cost of entry and require space in a laboratory. These challenges limit tracking the evolution of viral outbreaks in more remote and low-resource areas. As the MinION is so portable, it was a game-changer for in-field sequencing during viral outbreaks.

The minION was used during the Ebola virus outbreak of 2013-2016 in West Africa, and again during the Zika virus outbreak in Brazil in 2016. The protocols developed during the Ebola and Zika outbreaks were able to be quickly adapted by a genomics research group, the Artic Network, for sequencing of SARS-CoV-2.

Typically the advantage of using Nanopore sequencing is that it is able to sequence long fragments of DNA. This makes it easier to identify overlapping fragments and reduces ambiguity in genome assembly. However, as SARS-CoV-2 undergoes PCR prior to sequencing, the advantage in this instance is the availability of both portable and high throughput devices. The functionality during this pandemic was to sequence small numbers of viruses, less than 50 per minion flow cell within 16-24 hours. This had massive implications in supporting infection control teams, both clinically and regionally. Being able to scale up lower throughput approaches by using a GridION enables rapid response for smaller investigations. Larger epidemiological studies with big batches of samples can then be run more efficiently and cost-effectively on platforms such as NextSeq.

The advancements in portable sequencing devices have opened up new possibilities for sequencing organisms in the furthest corners of our planet. The accuracy of genetic sequencing is improving continuously and the future for Nanopore Technology is promising and exciting for all those who are part of the current genetic sequencing revolution.

Using metagenomics to investigate infections

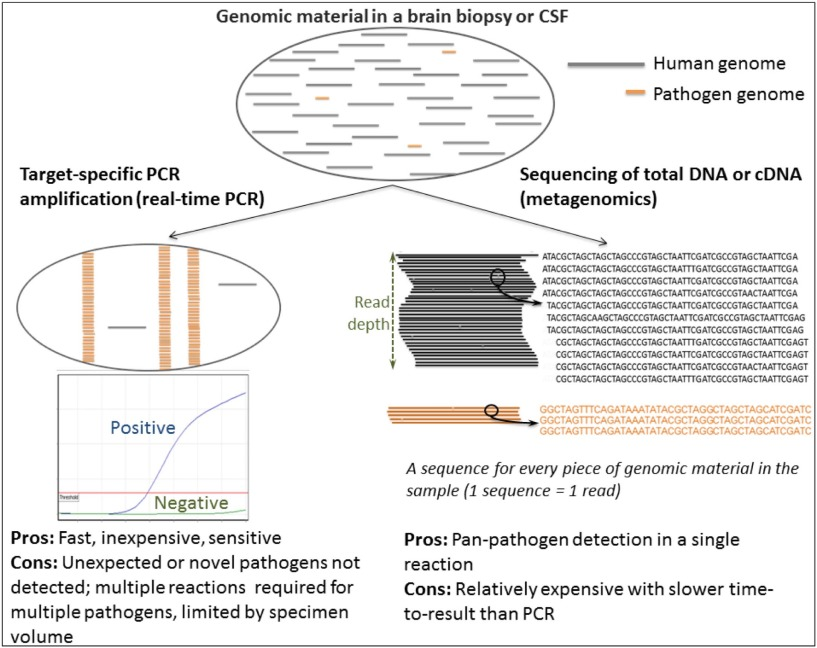

The gold standard for diagnosis or detection of viral infection is targeted PCR (polymerase chain reaction) to amplify and detect small regions of the DNA or RNA of specific viruses. Real-time PCR is fast, with results in as little as 1–2 hours and inexpensive, starting at only £2 per reaction for laboratory-developed tests (LDTs). PCR assays are designed to target the organism of interest so are highly specific and can detect as little as one target copy per reaction so are very sensitive. In syndromes that are well characterised with infections largely caused by known and expected viruses, PCR is unrivalled.

However, some syndromes such as neurological infections in immunocompromised patients can be caused by hundreds of different pathogens including viruses, bacteria and parasites. In these instances, there is often insufficient specimen available to test for every possible organism, especially since PCR reactions are limited to just a handful of targets per reaction. Consequently, in the majority of cases of encephalitis, the causative agent is not known. In these instances, metagenomics is increasingly being applied to aid in the diagnosis of infection.

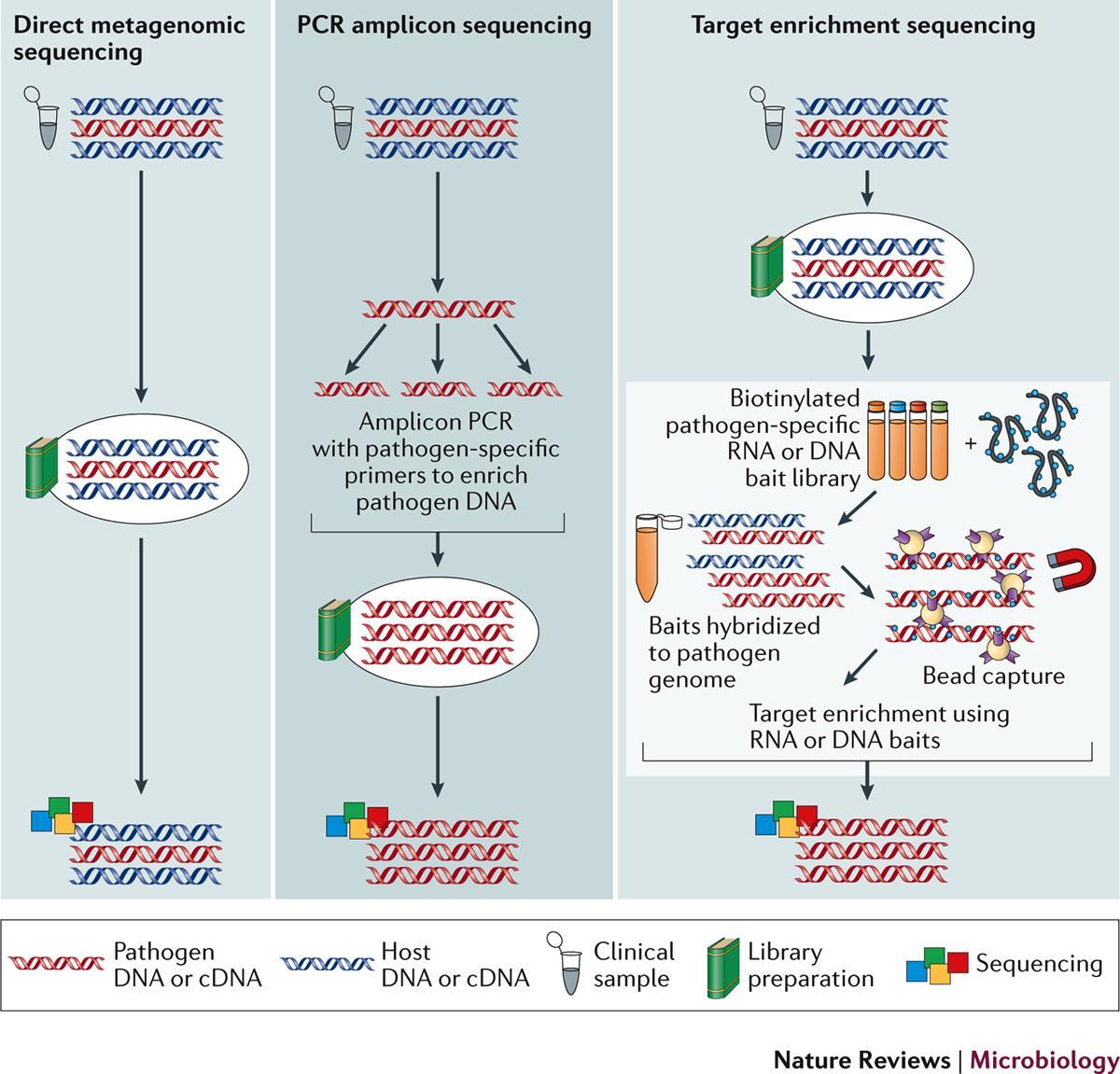

Metagenomics is the deep sequencing of all of the genetic material in a specimen. Following depletion of host DNA and RNA, sequencing libraries are prepared from the remaining DNA and RNA. This will include residual human DNA and RNA but also the DNA and/or RNA of any organisms present in the specimen. The sequences generated are compared to a database of known sequences to identify any organisms present.

The main advantage of metagenomics for the diagnosis of infection is it requires no prior assumptions about the organism causing infection. With PCR we have to think of the likely aetiologies and test for them, which may or may not yield an answer.

Conversely, since metagenomics is untargeted, any organism will be identified so long as there is some similarity to sequences in the analysis database. This means rare, unexpected or novel organisms can be identified. In addition, when an organism is identified, assuming the viral load is high enough, sequence data for that organism will be generated which can inform typing, molecular epidemiology and/or genotypic resistance analysis. This was the approach used to initially determine the SARS-CoV-2 genome sequence.

The primary advantage of using metagenomics to diagnose infection is that it is untargeted. However, it is the untargeted nature of the technique that also leads to its main disadvantage. Despite the depletion of human DNA and RNA prior to sequencing library preparation, the vast majority of data sequenced is of human origin, with as little as 0.000002% of sequences belonging to the causative organism. Identifying this ‘needle in a haystack’ requires a depth of sequencing which comes at a substantial cost compared to PCR and can result in only a small amount of sequences generated for the organism of interest (Figure 9).

Source: Journal of infection

Download Figure 9 alt-text here

Further reading

Astrovirus VA1/HMO-C: an increasingly recognised neurotropic pathogen in immunocompromised patients

Norovirus whole genome sequencing by SureSelect target enrichment: a robust and sensitive method

Beyond viruses: clinical profiles and etiologies associated with encephalitis

The epidemiology of acute encephalitis

Metagenomics for neurological infections – expanding our imagination

A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019

A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China

Using sequencing to investigate SARS-CoV-2

Sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 allowed for the rapid identification of the virus and the development of diagnostic tests and other tools for a rapid response to the pandemic.

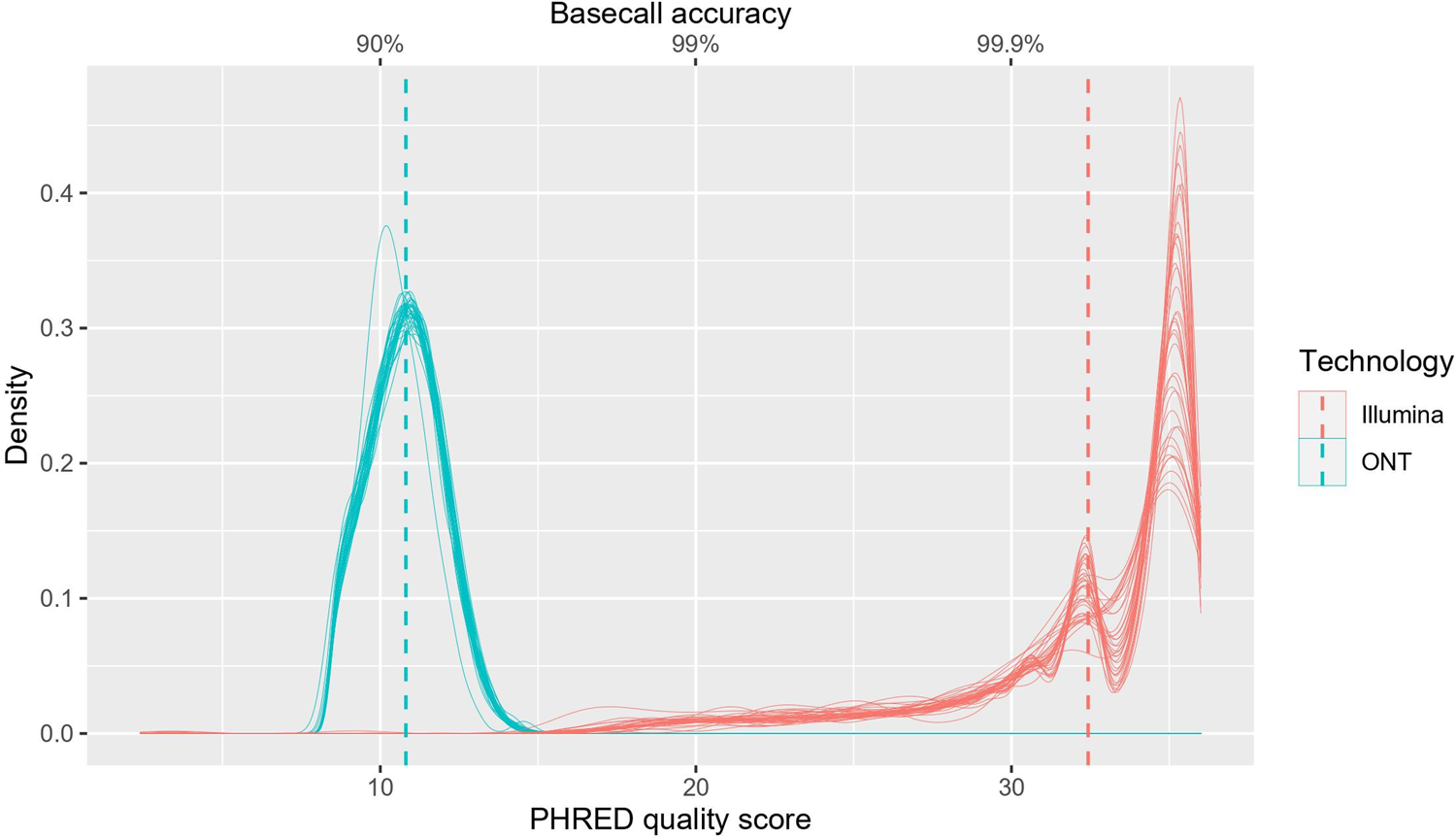

The sequences were determined using a range of experimental approaches based on metagenomics, sequence capture or enrichment, amplicon pools by deploying short (e.g., Illumina) or long-read (e.g., Pacific Biosciences, Oxford Nanopore Technologies) sequencing platforms. Many sequencing platforms are currently used to sequence the SARS-CoV-2 virus, including Sanger, Illumina, ION torrent, and Oxford Nanopore Technology, which have their advantages and disadvantages. Short-read sequencing technologies (e.g., Illumina) enable accurate sequence determination. However, long-read sequencing devices from companies such as Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) offer an alternative with several advantages. ONT small throughput devices are portable, cheap, require minimal supporting laboratory infrastructure or technical expertise for sample preparation, and can be used to perform rapid sequencing analysis with flexible scalability. However, ramping up to higher throughput using ONT using PromethIon for example, removes the portability advantages and requires similar laboratory infrastructure to generate the required libraries.

A major challenge with whole-genome sequencing (WGS) is obtaining whole viral genomes from clinical samples promptly. Illumina SARS-CoV-2 sequencing is generally limited by long sequencing times and the high cost and labour associated with library preparation for high-throughput sequencing. Another limitation is their relatively short reads (2 × 300 bp), as genomes generally contain multiple repeated sequences, known as tandem repeats, that may be longer than the NGS reads and may result in gaps and misassemblies. Owing to the large footprint of most sequencers portability can be a challenge, which is unfortunate as there is generally a large distance between sample collection sites and sequencing laboratories.

Nanopore sequencing overcomes these challenges as they sequence in real-time and are long-read sequencing technologies that allow for portability and have a relatively low initial investment on sequencing equipment with the MinION costing $1000. ONT sequencing has, however, traditionally been limited by the high number of single pass false negatives and low sensitivity.

Short-read sequencing technologies are useful for population-level genetic analysis and clinical variant discovery as they provide low-cost, high-accuracy data when done in large batches. Long-read sequencing approaches, however, are well suited for de novo genome assembly, sequencing of genomes with long repetitive regions, copy number alterations, and complex structural variations. However, overwhelmingly during this pandemic, whichever platform has been used, short-read sequencing via an amplicon-based approach has been used to generate viral genome sequences. All ARTIC amplicons are under 500 bases and both ONT and Illumina have kits to deal with this. Longer read options such as the midnight protocol have recently emerged, though, as with all approaches, they are limited by RNA quality, which has been a particular issue due to the variety of lysis buffers deployed globally for diagnostic tests.

Several studies have compared the sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 between Illumina and ONT platforms and have shown that despite the higher single-pass error rates observed with ONT sequencing, highly-accurate SARS-CoV-2 consensus genomes can be achieved. ONT sequencing, however, failed to detect short indels identified by Illumina sequencing. There has also been a lower raw-read accuracy with nanopore sequencing when compared to Illumina sequencing.

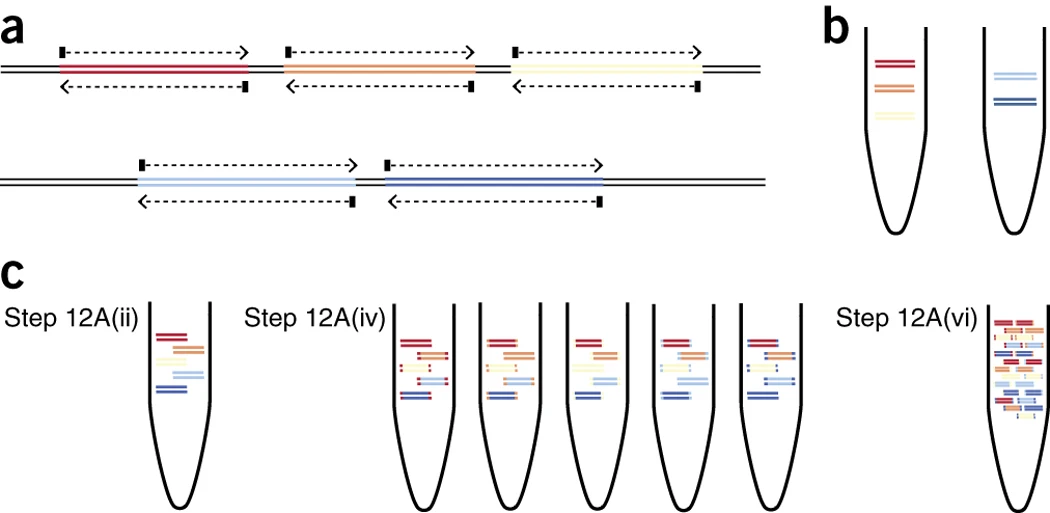

A comparison of SARS-CoV-2 WGS genomic coverage and variant detection between Illumina and Nanopore sequencing is necessary as it allows us to determine whether SARS-CoV-2 genomes produced by Nanopore sequencing can be reliably used for genomic surveillance and the development of diagnostic measures (Figure 12).

Source: PLoS One

Download Figure 12 alt-text here

Table 1 - Comparison of Illumina and Nanopore-based sequencing approaches for SARS-CoV-2 sequencing

| Testing Needs | Illumina – Amplicon sequencing - Illumina iSeq100 | Nanopore – Arctic and Midnight protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Instrument specification | Miseq, iSeq, Hiseq; 1536 to 3072 results can be processed on the NovaSeq 6000 system in 12 h using; two SP or S4 reagent kits or 384 results in; 12 h using the NextSeq 2000 or the NextSeq 500/550/550Dx (in RUO mode); HO reagent kit | MinION, PromethION, GridION |

| Average read length | 150bp – 400bp | Variable up to 900 Kb |

| Base Error rate | 0.2% | 8.3% |

| Per-base error frequency profiles | Weaker correlation between replicates (substitution R2 = 0.15; indel R2 = 0.42) - indicating that short-read sequencing errors were less systematic than for ONT libraries | Clear correlation between ONT replicates (substitution R2 = 0.67; indel R2 = 0.82) - indicates that ONT sequencing errors are not entirely random but are influenced by local sequence context |

| Consensus-level sequencing accuracy | High across SARS-CoV-2 genome | High across SARS-CoV-2 genome |

| Median read depth | 4833X | 436X |

| Genome coverage at reads depth 100X | 96.7% | 94.9% |

| Limit of detection | <500 copies/mL | 10 copies/reaction |

| Turnaround time | ~ 24hr | ~ 9h |

Further reading:

A rapid, cost-effective tailed amplicon method for sequencing SARS-CoV-2

Nanopore sequencing of SARS-CoV-2: Comparison of short and long PCR-tiling amplicon protocols

Analytical validity of nanopore sequencing for rapid SARS-CoV-2 genome analysis

SARS-CoV-2 sequencing workflow

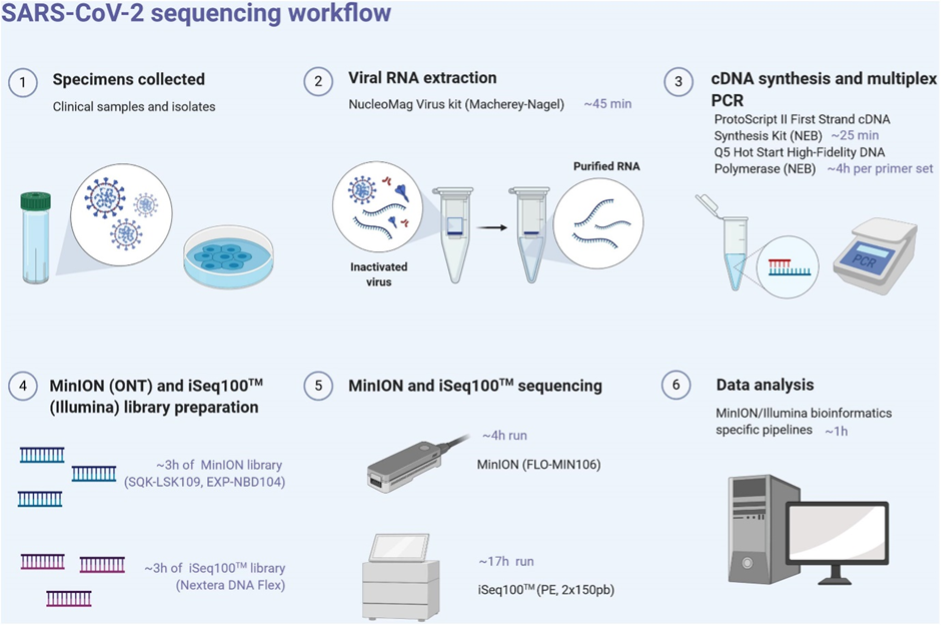

Here we outline one potential ARTIC workflow example (Figure 13). It must be noted that many different approaches, kits and methods have been used throughout the pandemic to good effect. Commercial kits provide an off-the-shelf option that can allow labs to start sequencing quickly. However, the lack of visibility around the primer design process increases the risk that all VOCs are not covered, and how quickly new VOCs are included is unclear. COG-UK in particular was able to be so adaptive due to the ongoing work of the ARTIC network and constant primer design activities led by the University of Birmingham.

Download Figure 13 alt-text here

For each sample, the LunaScript RT Supermix kit (New England Biolabs, NEB, United States) is used to obtain single-strand cDNA from RNA extracts using random hexamers and poly-dT primers, allowing even coverage across the length of the RNA targets. RT was performed at 25°C for 2 min, 55°C for 10min and 95°C for 1 min. Pools of specific primer sets were used to generate amplicons from the cDNA using the Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB, United States). These multiplex primer sets (divided into two separate pools) were designed using the Primal scheme software on the SARS-CoV-2 reference sequence (Genbank accession number NC_045512) to sequentially amplify either 400bp (ARTIC protocol) or 1200bp (Midnight protocol) using the following PCR conditions: 98°C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 98°C for 15 s, 65°C for 5 min, and ended by 65°C for 5 min. PCR products from both pools are mixed into one tube after successful PCR amplification.

Clean-up of PCR products was performed with AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter, United States). The quantity of amplicons was measured with the Qubit 2.0 fluorometer using the dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States), and the quality was assessed by electrophoresis. The amplicons obtained from the two clinical samples and their corresponding isolates were normalised to equal concentrations, multiplexed (X2), and sequenced using the MinION and Illumina System

SARS-Cov-2 viral genomes from patient samples:

Step 1: Extraction of viral RNA genomes

The viral RNA genome is typically extracted from various VTM solutions of clinical COVID-19 samples. Samples should be stored at −80°C, thawed on ice, and kept cold to maintain viral genome integrity

Step 2: Reverse transcription of viral RNA to cDNA

Following extraction, RNA is converted to cDNA as soon as possible, preferably without a freeze-thaw cycle, to prevent potential RNA degradation. Lunascript RT SuperMix kit (New England Biolabs) is commonly used because of the short reaction time and single master mix containing dye, which accelerates and simplifies the workflow and reduces contamination potential.

Step 3: qPCR to approximate viral load

To quantify approximate viral load in each sample, qPCR is performed using cDNA as template using any commercially available or in-house kit

Step 4: Multiplex ARTIC PCR to amplify viral genome sequences

Once qPCR is performed, viral genome cDNA is amplified to increase the copy number of viral genomes. Two pools of primers are designed by the ARTIC Network, which are commercially available from IDT as the ARTIC nCoV-2019 V3 primer set. These require two pools of PCR reactions for every sample, with pool 1 containing 55 primer sets and pool 2 containing 54 primer sets. Two primer pools are used to create overlapping amplicons that reduce interference during PCR and prevent short overlapping products from being preferentially produced. Through this tiling amplicon scheme, complete coverage of the genome is achieved. Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase from New England Biolabs (NEB) is used commonly for PCR reactions

Step 5: Pooling and purification of ARTIC PCR products

Before library preparation, pool 1 and pool 2 of ARTIC PCR reactions are combined for every sample and the ~400 base-pair (bp) amplicons are purified from contaminating PCR reactions using SPRI AMPure XP beads (Beckman-Coulter).

Step 6: Fluorescence-based qubit quantification of pooled and purified ARTIC PCR products

The purified PCR pools are quantified using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer and Qubit dsDNA High Sensitivity (HS) Assay Kit following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol

Step 7: Preparation of DNA ends for barcoding

Following the approximation of pooled PCR product concentration by Qubit, 60 ng of pooled and SPRI purified PCR amplicons from SPRI clean-up are added to the end preparation reactions designed to create compatible ends of the DNA amplicons for sample barcoding. These are referred to as end-prep reactions. The DNA is first end-repaired followed by dA-tailing and inactivation of end-repair enzymes. Ultra II End-Prep kit from NEB most widely used following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. After this step, DNA can be frozen at −20°C but is most often kept at 4°C for all downstream library preparation steps.

Step 8: DNA library sample barcoding and adapter ligation

To sequence a full 96-well plate of samples, each sample must be uniquely barcoded and later demultiplexed by allocating reads to samples with the matching barcode. This reduces the overall cost per sample and allows sequencing of up to 96 samples in a single run. To achieve this, Rapid Barcoding Expansion 96 kit (EXP-NBD110) from ONT is widely used for nanopore sequencing and Illumina based CovidSeq kit is used for Illumina platform. After individual barcoding reactions are performed in a 96-well plate, all samples are pooled and cleaned with SPRI beads. After barcoding and clean-up, ONT adapters are then ligated to each amplicon end for the pooled libraries in a single reaction.

Step 9: Loading and running the MinION/Illumina system

For optimal performance on a MinION instrument, 20 ng of adapter-ligated library should be loaded onto the flow cell. Overloading the flow cell results in lower throughput. Therefore, a final Qubit quantification is performed. The DNA sequencing library is then prepared using ONT reagents/Illumina reagents following recommended protocols.

Step 10: Sequencing, real-time visualisation, and data analysis

Step 11: Phylogenetic analysis, variant calling, and database deposition of SARS-CoV-2 genomes

Why you should collect metadata

To ensure that SARS-CoV-2 genomic data are as useful as possible, they should be accompanied by appropriate metadata (Table 1). Curating metadata and sharing them locally or publicly can be time-consuming, but both are an integral part of any sequencing pipeline. The required resources should be allocated when the study is being designed.

Metadata should include, as an absolute minimum, the date and location of sample collection. However, the release of additional metadata greatly increases the potential applications of a genomic sequence. Where possible, therefore, information on specimen type and how the sequence was obtained in the laboratory should be included (Table 2). Duplicate samples from the same individual or duplicate sequences from the same sample should be clearly identified. Demographic and clinical information, such as age, sex, presence of co-morbidities, disease severity and outcome, and links to other sequences in the database, are encouraged where such information does not risk identifying the patient.

A global consensus on specific formats for metadata (such as date) would allow genomic sequence data from many different laboratories to be rapidly compiled into larger data sets and reduce ambiguity. Also, care should be taken if using Microsoft Excel to ensure that automatic format changes to date do not occur. Some consensus genome repositories, including GISAID, already place format restrictions on certain fields. If data repositories do not already impose formats, the format restrictions for SARS-CoV-2 shown in Table 2 are suggested. Table 2 also highlights examples of analyses that require the provision of specific metadata.

WHO strongly encourages rapid public sharing of sequences and metadata (section 4). However, it is vital to protect patient anonymity. Laboratories should carefully consider whether patients could be identified if all available metadata are shared together. Where few COVID-19 cases have been observed, there is a greater risk of patient anonymity being compromised and therefore fewer data can typically be shared. Where it is judged inappropriate to share detailed metadata via publicly available repositories, it may nevertheless be appropriate to grant access to a small number of users via secure locally developed platforms.

Where it is not possible to share all metadata without risking patient confidentiality, the data that are most useful for global studies should be preferentially shared. For example, sampling location, date and travel history are more useful for phylodynamic studies than patient age or sex (Table 2).

Some laboratories choose to add jitters (noise) to provided dates to decrease the chance that patients can be identified. This can be achieved by a number of methods, for example, by choosing a false date within 5 days on either side of the date of sample collection, or by using the sequencing date as the sample date. Such practices negatively affect molecular clock-based phylogenetic inference and should ideally be avoided. If, nevertheless, this practice is followed, information on exactly how the new date was selected should be provided as a note.

Table 1 - Sample-specific metadata format and use

| Metadata type | Recommended format if applicable | Analyses for which the metadata are required |

|---|---|---|

| Date of sample collection | YYYY-MM-DD; If the date of sampling is unavailable, date received by testing laboratory could be adopted as an alternative, but this should be clearly indicated | Molecular clock phylogenies (including any models implemented in BEAST or BEAST2). These can provide estimates of dates of introduction, changes in outbreak size over time and evolutionary rate |

| Location | Continent/country/region/city. For discrete phylogeographical analyses (section 5.4.3), location resolution can be low (e.g. country level information for consideration of movement between countries) but higher resolution data is preferable to allow finer-scale analyses. Continuous phylogeographical approaches typically require relatively high-resolution data (e.g. city or municipality) | Any phylogenetic interpretation of global or regional virus spread (including models in BEAST or BEAST2) |

| Host | For example, human or Mustela lutreola | Host range and virus evolution |

| Patient age | For humans, give age in years (e.g. 65) or age with unit if under 1 year (e.g. 1 month, 7 weeks). For non-human animals, juvenile or adult | Descriptive epidemiology or as a possible trait for discrete phylodynamic inference |

| Patient age | For humans, give age in years (e.g. 65) or age with unit if under 1 year (e.g. 1 month, 7 weeks). For non-human animals, juvenile or adult | Descriptive epidemiology or as a possible trait for discrete phylodynamic inference |

| Sex | Male, female or unknown | Descriptive epidemiology |

| Additional host information | No standard format. For animals, this may include context, such as “domestic - farm”, “domestic - household”, “wild”, etc. | Disease surveillance in human or animal hosts |

| Travel history | No standard format. Travel history in the 14 days preceding symptom onset should be obtained from patients where possible. Deliberate release of travel history only to a low resolution (e.g. country) may be important to protect patient confidentiality | Phylogeographical or phylodynamic analyses directed at estimating transmission rates or routes between regions |

| Cluster or isolate name | No standard format. Appropriate formats may include “Same epidemiological cluster as sample X”, “Same patient as sample X”, or “Sample from patient XYZ” (where XYZ is an anonymized identifier that cannot be traced back to the patient or used to access other patient data that might compromise confidentiality) | Phylogenetic downsampling to ensure the appropriateness of phylodynamic models. Cluster investigation |

| Date of symptom onset | YYYY-MM-DD | Specialist phylodynamic applications that investigate transmission clusters |

| Symptoms | No standard format. Appropriate degree of symptoms; may include “severe”, “mild” and “out of norm” | Descriptive epidemiology |

| Clinical outcome if known | No standard format. Appropriate formats may include “recovered”, “death” and “unknown” | Descriptive epidemiology |

| Comments | No standard format. Appropriate comments may include how samples were selected (e.g. “cluster investigation”, “randomly”), or the storage location of other data files, such as raw read data | Interpretation of data quality or utility |

Table 2 - Sequence-specific metadata format and use

| Specimen source, sample type | Recommended format if applicable | Effect of cell tropism |

|---|---|---|

| Passage details, history | No standard format. It is important to indicate that cell culture was conducted (e.g. “Cultured”); ideally, this information should include the type of cells used and the number of passages | Removal of cell-cultured viruses (which may have induced genetic changes) |

| Sequencing technology | No standard format. Ideally, this should include the laboratory approach and sequencing platform (e.g. “Metagenomics on Illumina HiSeq 2500” or “ARTIC PCR primer scheme on ONT MinION”) | Sequencing artefacts |

| Assembly method, consensus generation method | No standard format | Sequencing artefacts |

| Minimum sequencing depth required to call sites during consensus sequence generation | e.g. 20x | Sequencing artefacts |

Extensive data should be shared as patient anonymity is typically unaffected. However, sharing all of the information listed in this table might compromise patient anonymity. Therefore, an ethical review should be conducted to determine which metadata can be safely shared. It may be appropriate to share less data on public databases than on databases that are held and analysed locally.

Download an example of metada form here

How to handle primary samples

In this video, laboratory scientists from Parul University demonstrate the collection, preparation and transport of SARS-CoV-2 primary samples. Rules and PPE requirements will differ between countries, states and times in the pandemic. This video was created when healthcare professionals required full PPE for taking swabs, whereas now we may be used to self-swabbing at home. Always check local guidance for each activity.

Storing high-quality samples

Most of the current knowledge on diseases and the consequent diagnostic and therapeutic possibilities is based on the study of biological samples and the data associated with them. Following the exceptional health emergency caused by the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic, unprecedented action is underway to collect biological samples and related personal and health data from the population. These samples and data, collected for diagnostic procedures and the consequent care of the affected people are also pivotal for effective research to defeat COVID-19.

In this context, structuring a coordinated and extensive collection, handling and storage of samples (nasopharyngeal swabs, sputum, blood and its derivatives, broncho-alveolar lavage, post-mortem tissues, etc.) from all the infected and recovered populations takes priority. It is crucial to collect and store the biological materials of the population concerned according to the established international criteria, and in compliance both with ELSI (ethical-legal social) requirements and the rights of the patients involved, in order to make them available over time for collaborative research projects.

From this perspective, it is recommended to store COVID-19 samples according to prevailing country requirements, and quality standards in a stable and continuous manner for future research and/or diagnosis. Inadequate or inappropriate patient specimen collection, storage, and transport are likely to impact specimen quality and yield false test results. Therefore, training in specimen handling is highly recommended, and there is a critical need for tight environmental uniformity to ensure specimen viability. This article gives a brief overview of collecting, transporting, and storing COVID-19 specimens.

Specimen storage

In order to ensure accurate results, it is essential to understand and implement the storage and transport conditions mandated by the regulatory bodies.

According to the interim guidance provided by WHO, specimens for virus detection should reach the laboratory as soon as possible after collection.

In addition, as per official guidelines, specimens that are delivered promptly to the laboratory can be stored and shipped at 2-8°C.

However, when there is a higher likelihood of delay in the specimens reaching the laboratory, the use of viral transport medium is strongly recommended.

Specimens may be frozen to -20°C or ideally to -70°C and shipped on dry ice if further delays are expected.

Table 1 - Specimen Collection and Storage

| Specimen type | Collection materials | Storage temperature until testing in-country laboratory | Recommended temperature for shipment according to expected shipment time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab | Dacron or polyester flocked swabs | 2-8 °C | 2-8 °C if ≤5 days; –70 °C (dry ice) if >5 days |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage | Sterile container * | 2-8 °C | 2-8 °C if ≤2 days; –70 °C (dry ice) if >2 days |

| (Endo)tracheal aspirate, nasopharyngeal or nasal wash/aspirate | Sterile container * | 2-8 °C | 2-8 °C if ≤2 days; –70 °C (dry ice) if >2 days |

| Sputum | Sterile container * | 2-8 °C | 2-8 °C if ≤2 days; –70 °C (dry ice) if >2 days |

| Tissue from biopsy or autopsy including from lung | Sterile container with saline or VTM | 2-8 °C | 2-8 °C if ≤24 hours; –70 °C (dry ice) if >24 hours |

| Serum | Serum separator tubes (adults: collect 3-5 ml whole blood) | 2-8 °C | 2-8 °C if ≤5 days; –70 °C (dry ice) if >5 days |

| Whole blood | Collection tube | 2-8 °C | 2-8 °C if ≤5 days; –70 °C (dry ice) if >5 days |

| Stool | Stool container | 2-8 °C | 2-8 °C if ≤5 days; –70 °C (dry ice) if >5 days |

| Urine | Urine collection container | 2-8 °C | 2-8 °C if ≤5 days; –70 °C (dry ice) if >5 days |

- For transport of samples for viral detection, use a viral transport medium (VTM) containing antifungal and antibiotic supplements. Avoid repeated freezing and thawing of specimens. If VTM is not available, then sterile saline may be used instead (in which case, duration of sample storage at 2-8 °C may be different from what is indicated above).

Aside from specific collection materials indicated in the table, also assure other materials and equipment are available: transport containers, specimen collection bags and packaging, coolers, cold packs or dry ice, sterile blood-drawing equipment (e.g. needles, syringes and tubes), labels and permanent markers, PPE, materials for decontamination of surfaces, etc.

Before storing samples, you should consider:

How long should the samples be stored?

Should there be a differentiation between positive and negative samples (and non-conform or inconclusive results)?

Are there any other guidelines for storing the samples?

Reasons for storage of samples

Clinical specimens or a subset of the clinical specimens may need to be retained for various purposes such as performing additional tests, for quality control purposes, or for use as control materials to assess newer diagnostic tests.

In addition, a laboratory may need to store specimens for projects aimed at studying genomic epidemiology of the SARS-CoV-2 virus across regions and over time

Existing guidelines: storage duration

The WHO or ECDC do not have guidelines about the duration of storage of COVID-19 PCR samples.

In August 2020, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Government of India, advised government laboratories to retain all positive COVID-19 samples at ultra-low temperatures for 30 days, then disinfect the samples before disposal. Some respiratory samples will need to be kept even longer — even a year or more — in ultra-low temperature freezers, for future testing and quality control purposes.

According to the new ICMR guidelines, all samples in long-term cold storage must be appropriately labelled with laboratory identifiers and collection dates. Positive COVID-19 test samples must be kept in -80 C deep freezers.

Beyond that, ICMR says many positive COVID-19 samples must be kept in government laboratories for one year. The number of retained samples will vary among laboratories, but ICMR is looking for 50 positive samples at each laboratory, or 1–2% of total monthly samples, or whichever is smaller.

Existing guidelines: storage conditions

WHO recommends the storage of dacron or polyester flocked swabs with a viral transport medium (VTM) containing antifungal and antibiotic supplements for up to 12 days until analysis at 2-8°C. If phosphate buffered saline is used instead of VTM, it recommends storage for up to 7 days at 4°C.

In case other viruses such as influenza should also be tested, the WHO recommends storage of samples for no longer than 5 days at 4-8 °C, counting from the date of sampling until analyses.

ECDC recommends that all specimens should be stored at 2-8°C for up to 48 hours after collection. For handling or shipping after 48 hours, storage at -70°C (dry ice) is recommended.

Storage of Specimens

Specimens must be stored in containers with adequate strength, integrity and volume to contain the specimen, leak-proof when the cap or stopper is correctly applied, made of plastic whenever possible, free of any biological material on the outside of the packaging, correctly labelled, marked and recorded to facilitate identification, and made of an appropriate material for the type of storage required.

Set the temperature for shipment in line with the expected shipment time.

Avoid repeated freezing and thawing.

At least two aliquots of VTM should be made before the specimens are stored or shipped. One of two aliquots should be stored at −70°C or −80°C as soon as possible.

Storage of Nucleic acid extract:

The RNA from the viral specimen is extracted and stored at -80°C or lower freezer.

Storage of cDNA product:

The amplified cDNA used for SARS-CoV-2 genome amplification is stored at -80°C in a freezer.

Specimen handling of SARS-CoV-2 samples

Personnel collecting the specimens should wear appropriate PPE (N95, KF94, or equivalent respirators, protective clothing, disposable gloves, etc.) and handle the specimens in a Class II or higher biosafety cabinet (BSC) at a biosafety level 2 (BL2) laboratory.

Aerosol-producing procedures should always be performed within the BSC.

If the container has to be opened outside of the BSC, PPE, such as an N95, KF94, or a higher-grade respirator (powered air-purifying respirator recommended), should be worn by the personnel and the bench should be disinfected after the procedure.

Personal hand hygiene: Wash hands thoroughly, preferably with warm running water and soap, after handling biological material and/or animals, before leaving the laboratory and when hands are known or believed to be contaminated.

All work surfaces and equipment to be disinfected with appropriate disinfectants.

Controlled ventilation system - A controlled ventilation system maintains inward directional airflow into the laboratory room.

Further reading

China CDC COVID-19: Laboratory Testing Guideline

US CDC Interim Guidelines for Collecting and Handling of Clinical Specimens for COVID-19 Testing

PHE UK Packaging requirements for COVID-19 samples

WHO Guidance on regulations for the transport of infectious substances 2019 – 2020

WHO Diagnostic testing for SARS-CoV-2: Interim guidance September 2020

ECDC Laboratory support for COVID-19 in the EU/EEA

What happens to samples after sequencing

We invited leading scientists from Bangladesh, Brazil, India and Nigeria to share their knowledge and experiences implementing SARS-CoV-2 sequencing in their institutions. Watch Dr Senjuti Saha, Prof Paola Resende, Dr Murali Dharan Bashyam and Prof Christian Happi discussing what the final destination of sequenced samples is in their facilities.

The storage of samples will be guided by local and regional ethical approval and regulation. For example, in the UK, COG-UK consortium laboratories had to destroy all primary viral samples by March 2022 but could retain stored nucleic acids until September 2022 without applying for additional approval. Public Health Agencies will have more flexibility in the length of their sample storage than Academic institutions, however the sheer number of samples generated during this pandemic means that physical storage space is a significant barrier to keeping all samples long-term. Clinical samples should be kept long enough for re-testing of failed or important samples if required and a selection of important samples (different lineages, CT values, priority settings) kept longer term for research and development.

Biobanking of samples has been widely utilised during the pandemic, but with this comes many ethical considerations, particularly when considering the interactions between high income countries and other partners to avoid biopiracy.

How to implement quality management

To ensure that work is performed accurately and consistently, it is important to put quality management systems in place. This limits error and expedites troubleshooting, thus saving resources on repeating failed experiments. Here are some ideas and suggestions for ensuring high-quality testing of SARS-CoV-2 samples.

Single-use aliquots and batch numbers

Create a reagent spreadsheet. Split your reagents into single-use aliquots and assign a unique batch number. Give each reagent a sequential ID i.e. QA-001, QA-002, and label with the relevant information (e.g. ID, expiry date and volume). Some reagents, such as a large bottle of nuclease-free water, cannot be completely dispensed in one go. To ensure multiple aliquot events from the same bottle are captured, assign each aliquot event with a sequential letter, i.e. QA-001-A, QA-001-B. Without this, it could seem as though a fresh bottle of water had been used for each set of aliquots, which could cause confusion when troubleshooting.

Record Keeping

The majority of good quality management is record keeping. The more detail you can record when performing your experiment, the easier it is to troubleshoot.

Assign each library a unique ID, i.e. EXP-001, EXP-002, as this makes it much easier to track experiments. Create a detailed experiment plan.

Create a way of capturing all the information for each library preparation. One method is to create tick-sheet versions of the protocols (see additional resources) with space included to record all reagent batch numbers, DNA quantifications and calculations. Whenever something does not go to plan, this should be recorded. The tick sheet can be fixed to the outside of the cabinet with a magnet, and each step crossed off as you go, thus reducing the opportunity for error. Paperwork should be checked and counter-signed by another member of staff to capture any errors.

Equipment

Ensure that equipment is well maintained, calibrated, and that staff have been properly trained in how to use it. Assign equipment unique equipment numbers, i.e. UE-001, UE-002. Record which specific items of equipment you have used throughout your experiment to help expedite troubleshooting.

Training

To reduce variation in results between operators, give all staff members the same level of training. Ideally, the protocol should be observed first and then performed with supervision until the staff member is able to perform the work without any guidance.

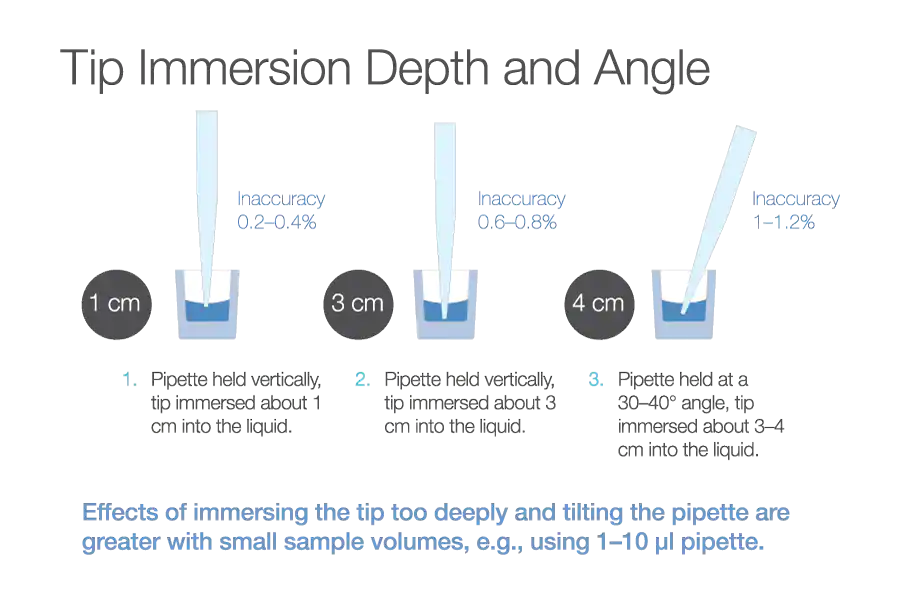

Consider training staff in pipetting techniques to ensure consistency and accuracy. Holding the tip vertically, having a 1cm immersion depth, and pre-rinsing tips to break surface tension before aspirating can all improve accuracy (Figure 14). For small volumes and repeat pipetting the reverse pipetting technique can be useful.

Source: Thermofisher

Download Figure 14 alt-text here

Quality Control Checks

Include negative and positive controls and take them through your whole process from reverse transcription to library preparation. After the PCR step, quantify the negative and positive controls on the Qubit Fluorometer (or equivalent method) and look for irregularities. It is important to also test a couple of samples, including both primer pools. Ensure that both primer pools have similar DNA concentrations. If reagents have not been properly mixed before dispensing this can lead to an imbalance between the primer pools. Controls are essential for quality management and for troubleshooting.

Assessing the quality of nucleic acid

The quality of a sample is measured at several checking points throughout the sequencing process. In this video, you will learn with Dr Paola Niola how to use Qubit and TapeStation methods.

The BioAnlayser is another fragment analyser which can be used as an alternative to the TapeStation. The main advantage of using the fragBioanalyser over the TapeStation is that it has a lower limit of detection. However, it has a more complicated set-up, is less-throughput, and ‘chips’ cannot be re-used over multiple runs, unlike TapeStation ScreenTapes.

Have you ever used any of these methods? Use the comments to tell us if you have used other methods too.

Download the PDF slides about Qubit here

Download the PDF slides about Tapestation here